Matt Harrison Clough for Insider

Anne-Marie Griger's job is to build big things — fields of solar panels that can power a city, forests of wind turbines as tall as sequoias. But to do it, she has to start small.

As a director of development for RES Group, one the world's largest privately-held builders of renewable-energy facilities, Griger has to figure out where, exactly, to put all the stuff we need to save us from a climate catastrophe. By some counts, that'll require 210,000 square miles of wind turbines and 15,000 square miles of solar panels. But they can't go just anywhere. The locations have to be windy enough for wind, or flat enough for solar. There needs to be a transmission line to connect to the power grid, so they can't be in the middle of nowhere. And finally, whoever owns the land has to agree to having a big energy project in their backyard.

Which, it turns out, is a huge problem.

In the vast empty spaces out West, odds are the land is owned by the federal government. That means a whole bunch of headaches. The National Environmental Policy Act and a dozen other federal laws set the rules for land use, and the paperwork — you wouldn't believe it. But if Griger tries to avoid federal permits by looking at private land, she has to navigate a ninja-warrior obstacle course of state and local rules, each with its own demands for setbacks and sightlines and time-consuming environmental studies. And even if all the individual landowners agree to host the project on their properties — in return for, say, a generous lease of $1 million a year for 30 years — getting a county permit still requires a public meeting. The bigger the project, the more likely the meeting will be a total shitshow.

"The most common people to show up are the adjacent landowners," Griger says. They always have concerns. Maybe she can make some changes to appease them. Or maybe she can cut them a check. But these days, Griger has found, a shocking number of locals aren't open to compromise. They're just dead set against seeing long rows of solar panels or power-line gantries next to their land, lined up like picket defenses against Godzilla. "Some people will be philosophically opposed to renewable energy," Griger says. "They think it's an Obama conspiracy. They think it's crazy, unproven technology. Other people say, 'I'm not opposed to renewable energy, I just think this is the wrong spot.' People always think their spot is unique."

Now bear in mind, when Griger builds something, she's paying the people near it for the privilege. And her projects don't leak toxic goo. They fight climate change, stabilize the energy grid, and power our lights and our phones and all the other things we demand from modern life. Yet it can be almost impossible to get them built. If the paperwork isn't approved, if the environmental studies turn up something endangered, if the meetings and lawsuits go on forever, then the project gets too expensive. If it doesn't pencil out, it doesn't happen.

"It makes me frustrated," Griger says. "Any time I tell someone that I develop renewable energy, they're always like, 'Oh, that's so cool.' And I say, 'Well, you're not at the public meeting where people are screaming at me that I'm going to give their kid cancer.'"

How did it come to this? This is the country that crisscrossed a continent with railroads, and then with highways. We cut a canal across Panama, dammed the Colorado to power the West, invented the skyscraper, and created the modern assembly line. We built Golden Gate bridges, sent rockets to the moon, put space stations into orbit, blanketed the Earth with a digital information network. Megaprojects are, like, our thing!

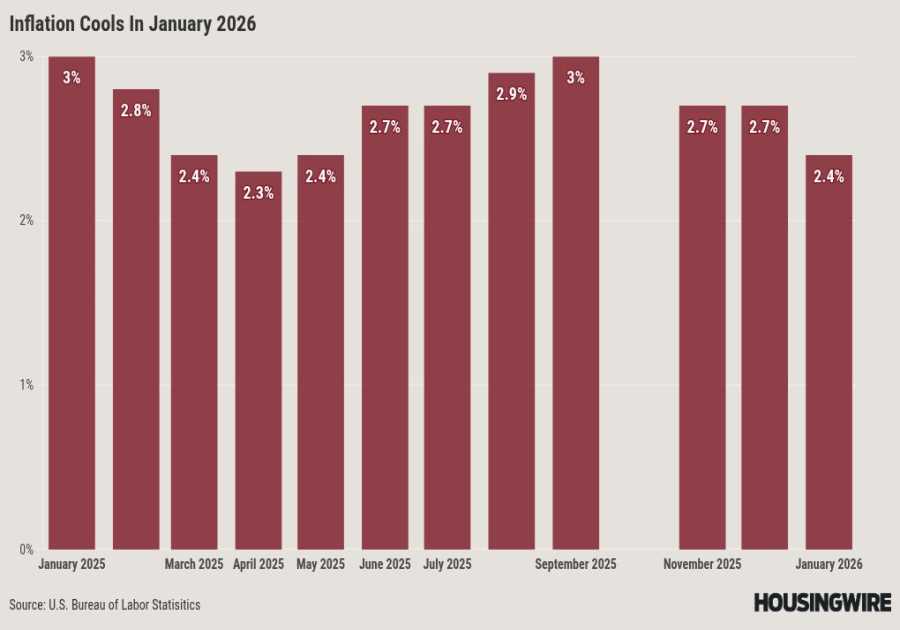

Except they aren't. For the past 50 years, we've been coasting. Without a massive national effort, our collapsing infrastructure — everything from power grids to sewers — will deprive us of $10 trillion in economic growth. We've deferred $157 billion in maintenance on decaying dams, and 220,000 bridges need fixing or replacing, at a cost of $319 billion. We face a shortage of more than 4 million homes, creating a crisis of homelessness and exacerbating income inequality. America is the sixth-most-expensive place in the world to build subways and trolleys. California has spent 15 years trying to build a 500-mile high-speed rail line connecting Los Angeles to San Francisco, now expected to cost $128 billion, quadruple the original estimate. In that same amount of time, China has built 23,500 miles of high-speed rail.

Our crisis of inaction threatens to cripple the economy beyond repair, condemn millions to poverty, and worsen the death toll from global warming. Floods, droughts, hurricanes, fires, heat waves — the bills from two centuries of burning fossil fuels are coming due. The solutions will cost trillions of dollars and require a pace of building unseen in America since World War II. To zero out carbon emissions, we need to build 100 gigawatts of new generating capacity — the equivalent of 100 nuclear power plants — every year until 2050. Yet at this moment of existential necessity, we're paralyzed. An offshore wind farm just broke ground after more than 20 years of bureaucratic dithering. If you want to supply America's homes and offices with clean energy, get in line: The average wait time to get a new project connected to the nation's mishmash of electrical grids is five years. Perhaps the single most pressing question we face today is: How do we make America build again?

Looking for answers, I talked to dozens of developers, economists, lawyers, policymakers, and researchers who work on infrastructure and megaprojects. I wanted to see whether there's a single, overarching way we can break through the complex logjam of idiocy and inertia that's preventing us from building all the housing and wind farms and chip factories and power lines we so desperately need. And I came away convinced that there is, in fact, a solution.

It's just not the one I expected to find. Or one I ever thought I'd agree with.

It's not really about the money. A megaproject, by definition, costs a metric shit ton of dollars to build. Let's say you wanted a 35-story spherical concert venue that could hold 20,000 people and have an exterior covered in 580,000 square feet of programmable LEDs. Well, that'll run you $2.3 billion. But if there are customers, there are investors — even with interest rates going up. As of September, you could go see U2 in that Sphere, if that's your thing.

Right now, money is on the table. The federal government has passed a bunch of laws — the Inflation Reduction Act, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act — that amount to more than $2 trillion of tax credits and grants to get America building again. But all those new projects are going to run headfirst into the same slow-moving bureaucracy that has always hamstrung major works — large or small, good or evil. Taking federal money means going through the federal permitting process that Griger and other developers hate. That's why the hot topic in Washington right now is "permitting reform."

Matt Harrison Clough for Insider

To a certain kind of policy wonk, permitting looks like an eminently solvable problem. If the accumulated bureaucratic cruft of the past 50 years has become too onerous, just scrape it off. Sometimes, that alone is enough to get things moving. Take the Pinedale, Wyoming, field office of the Bureau of Land Management, which encompasses Grand Teton National Park. From 2016 to 2019, researchers found, BLM field offices took between 106 and 220 days, on average, to process permits for oil and gas drilling. Pinedale's average: just 49 days. How? They used environmental studies they had already drawn up for previous projects to streamline the process, speeding up their analysis of how each new permit would impact a specific site. They were, in other words, efficient.

A team of researchers who studied the Forest Service found lots of other ways to speed up the permitting process. Setting hard deadlines for responses to applications helped, as did simple stuff like putting all the required permits in the right sequence. Having more people to handle all the paperwork would help — tucked into the Inflation Reduction Act is $1 billion for more "staff resources," to get the bureaucracy humming at a higher frequency. And better communication between agencies and applicants can make a huge difference. "Just doing that, you're moving permit times down from five years to two years," says Jamie Pleune, a law professor at the University of Utah who was part of the team that crunched the Forest Service data.

Washington is bursting with proposed reforms like this. Every ambitious politician, big-brained academic, and think tank worth its dark money has produced their very own white paper arguing for ways to tweak the rules. The massive engineering firm AECOM says it's all about policies to foster new engineering talent. The Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies says we need nationwide zoning reform to build affordable housing. The Brookings Institution recommends transferring oversight for the permitting of offshore wind farms to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, an agency I did not know existed until just before I typed this sentence. Even the White House has gotten into the act. After permitting screwups threatened to monkey-wrench President Joe Biden's building agenda, a senior administration official tells me that streamlining the permitting process is now a top priority.

What gets in the way of most projects isn't bureaucrats in Washington or environmental activists. It's pissed-off locals.

There's just one problem with all these proposals: They're Band-Aids for boo-boos, not a cure for what ails us. The reality is, only a tiny handful of megaprojects get slowed down by federal regulations. A not-yet-published analysis of nearly 2,000 wind and solar projects found that 95% of them either dodged all federal regulation or got streamlined review. Only 50 of the projects were challenged in federal court on environmental grounds. "That's a very different understanding of things than is commonly portrayed in the debate over permitting reform," says David Adelman, an environmental-law professor at the University of Texas who led the research. "For this class of projects, federal environmental laws are more the exception."

To get America building, we need to understand what actually gets in the way of most projects. It isn't bureaucrats in Washington, or counties with strict height limits on buildings, or environmental activists chaining themselves to pipelines. It's pissed-off locals, who don't want stuff — any stuff — built in their backyards.

One way America is exceptional is that, for better or worse, we believe landowners should have the final word on what happens to their land — or even, for that matter, the land next to their land. So we essentially allow any property owners who happen to be in the vicinity to have the final word on who can build what, and where. One researcher described this to me as a "veto gate." I call it vigilante enforcement.

Wealthy landowners on Nantucket who are worried about the view from their summer homes have delayed wind-turbine projects off the coast of New England for nearly two decades. Native American tribes have sued to prevent construction of solar panels in the Mojave Desert. Lawsuits filed by cities and landowners have blocked the bullet train from Los Angeles to San Francisco. New housing in almost every city faces constant legal challenges over density, shadows, or plain old vibes.

David Spence, a professor of energy law at the University of Texas who studies permitting and regulation, wanted to figure out who opposes which kinds of project. His database of more than 200 fossil-fuel and renewable-energy projects — and what more than 400 local and national environmental groups said about them — shows that national groups like Greenpeace or the Natural Resources Defense Council consistently fight the harmful stuff, like oil wells and fracking. But state and local groups made no such distinction. They mobilized against everything — including wind farms and transmission lines. And they usually did it by making bogus claims about health risks.

"If I don't want my viewshed interrupted by a wind farm, and I'm not getting a job or anything I see as a tangible benefit, why not say no?" Spence says. "Once you see it as something you're opposed to, you start to grab onto these other arguments that aren't logical or are not supported by science."

Sometimes people fight the projects we need, from wind farms and power lines to high-speed railways, under the auspices of federal environmental laws — the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, the Endangered Species Act. But a lot of other rules, federal and local, are also environmental regulations at their core. Siting rules dictate where you can put solar panels and wind turbines, and how far they have to be set back from other developments. Local zoning laws, from the outset, were superficially designed to give city dwellers access to open space, clean water, and homes free of disease and pests. Look close enough at any building regulation and you'll find a green agenda buried beneath all the red tape.

Matt Harrison Clough for Insider

I want to be clear here: We need laws that protect the environment. Without them we'd have dams in the Grand Canyon, no Yellowstone National Park, skies of smoke, rivers of sludge, cats and dogs living together, etc. They're what keep hog farms from putting giant pools of waste wherever they want. They're what closed the ozone hole, stopped acid rain, and might yet hold off the worst effects of the climate crisis.

But the problem is that these well-intentioned laws are designed, intrinsically, to say no — especially to human constructs like factories and cities. It says so right there at the top of the granddaddy of all environmental regulations, the National Environmental Policy Act. The biggest threats to the environment, NEPA states, are things like "high-density urbanization" and "industrial expansion" and "new expanding technological advances."

And there's the rub. Those things are also good. What sounded like environmental threats back when NEPA was signed into law in 1970 — Technology! Cities with lots of people! — are now the very things we need to save a world wracked by climate disasters and economic instability. What's more, the old environmental laws designed to protect nice clean "nature" from dirty old "technology" are now being used to shut down projects that pose no threat to the environment. Early this year, a state appeals court sided with a handful of Berkeley residents who sued to block proposed housing for 1,100 students at the University of California. Their grounds? That the state's Environmental Quality Act protected them from the noise pollution all those college kids would cause. In August, irate residents in Los Angeles used the Berkeley precedent to block housing for the University of Southern California.

Or take wind turbines. According to one study, opposition to wind farms comes not from longtime residents of rural areas, but from newcomers who moved to the countryside for the beauty of the surroundings. These people "may not only be wealthier, but perhaps also more likely to work from home than long-term residents and commuters," so they get cranky about how the wind turbines will ruin the views from their home offices. And those who are retired or semiretired "may also have more time to attend public meetings and the resources necessary to participate in online opposition efforts."

The point is, the broad environmental regulatory framework we put in place to fight pollution a half century ago has become a weapon of self-interest. "No nukes" and "save the whales" mutated from rallying cries to protect the Earth against rapacious development into a machine for saying no to change — even necessary change.

"No nukes" and "save the whales" mutated from rallying cries to protect the Earth into a machine for saying no to change — even necessary change.

"Before we had the National Environmental Policy Act, we were in a situation where we were not doing enough environmental consideration before we built things," says James Coleman, a professor of energy law at Southern Methodist University. "We have probably moved to the other side of the spectrum. Since NEPA passed in 1970, we've basically been running down our existing infrastructure." The broad environmental regulatory framework we put in place to fight pollution a half century ago has become a weapon of self-interest. "No nukes" and "save the whales" mutated from rallying cries to protect the Earth against rapacious development into a machine for saying no to change — even necessary change.

If we want to get America building again, we can't just tinker around with "permitting reform" or faster paperwork. The moment demands a bigger, more sweeping fix. It has to take into account essential new priorities, cut across warring jurisdictions, and move projects forward with the appropriate urgency. To construct the stuff we need to actually save the environment, we have to do something unthinkable. We have to demolish our existing environmental laws — top to bottom, federal to local — and replace them with something better.

Let's think about what a new environmental law would look like, if we set out to craft one for the age of climate change and income inequality and homelessness. Call it the National Ecosystems Conservation Act.

NECA would continue to vigorously safeguard the environment against pollution and degradation. It would protect grand open spaces and the creatures that live in them from abuse. It would prevent and punish dangerous pollution, especially in vulnerable communities and vulnerable places. Proposals for new projects would still have to show that they aren't harmful. This isn't some version of the utterly insane Republican plan reported to be in the works in case the GOP wins the presidency next year, which aims to kill any Biden program that contains the slightest whiff of carbon reduction and replace anyone who worked on them with oil-friendly apparatchiks. That would be bad.

But NECA would start by requiring policymakers, right from the start, to define the kinds of projects that are actually beneficial for the environment, and prioritize building the things that make that happen. Freeways, oil wells, incinerators, slaughterhouses? Put them through the regulatory wringer. Solar panels, power lines, more efficient urban housing? Take a hard look, but do everything you can to get them up and running, pronto.

Next, NECA would recognize that every project we cook up, no matter how much it might benefit the economy or the environment, is going to do some sort of harm. We already do this all the time — putting a price on an eagle, or the Badlands, or a kid dying of cancer. We even put a number on it. It's called the Value of a Statistical Life. If redesigning the guardrail on a freeway on-ramp costs more than the value of the lives it will save, it probably won't get built.

Right now, if the harm outweighs the good, we just shut down the project. Our current environmental laws turn everything into a yes-no equation. NECA would green-light projects that cause harm — provided that they mitigate that harm elsewhere. If you're building a wind farm, say, you acknowledge that it's going to kill some number of birds and bats. But instead of that being grounds for richy-rich neighbors to shut down the project, NECA would mandate that developers spend money somewhere else to cut down on the world's overall bird and bat deaths. The wind-farm developers, say, could be required to help reduce the global plague of outdoor feral and pet cats, which kill as many as 4 billion birds and 22 billion small mammals every year. Sure, you'll kill a few birds and bats with your wind turbines. But you'll more than make up for it by saving millions in other locations.

NECA would also limit the power of courts to review individual projects. Right now, courts have way too much power in determining how environmental laws get implemented. For clean-energy projects, they often wind up deciding to do something called a "hard-look review," which pretty much grinds everything to a halt. "If you read the National Environmental Protection Act, you would never guess that this is a statute that requires 10 years of study before you can build a bridge or a power line," says Coleman, the law professor. "That was more or less made up by the courts." NECA would take authority over project review away from the courts and lay out more explicitly what's required in an environmental review or a project approval. Permitting can't be bureaucratic improvisation.

Finally, and perhaps most important, NECA would limit the ability of locals to tank projects, and increase federal authority over essential infrastructure that crosses hundreds or even thousands of local and state jurisdictions. The new law would allow — mandate, even — public participation and comment. But it would set strict time limits on how long the back-and-forth can go on. Once everyone's had their say, and their concerns have been evaluated and either rejected or incorporated into the plan, the project would be allowed to move forward.

That's how we wound up with cellphones. Back in the days of Motorola flip phones, when local residents tried to use environmental laws to stop telecommunications companies from erecting a nationwide network of cell towers, Congress passed the Telecommunications Act of 1996. Cities and states were free to determine the aesthetics of cellular towers. People could make them look like a palm tree or whatever. But they couldn't just prohibit them, or file lawsuits based on wacky scientific claims about electromagnetic fields causing brain cancer.

Did it work? Tell you what, I'll do a TikTok about it. DM me after you watch it! I'm on Signal.

Matt Harrison Clough for Insider

Conservatives are likely to cry "states' rights" at the idea of giving the feds more power over infrastructure projects. But I didn't hear them griping about empowering the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to preempt state and local opposition to natural-gas pipelines. FERC doesn't just plop gas pipes anywhere; it's still required to consult with state and local authorities about the best places to put them. But in the end, FERC gets to say yes or no. The feds need to have the same power over other infrastructure projects that cross multiple jurisdictions — especially the stuff that's essential to modernize the grid and help prevent a climate catastrophe.

Danielle Stokes, a professor of environmental and property law at the University of Richmond, has written about the need to centralize the approval process for vital infrastructure — a school of thought known as renewable-energy federalism. "Until there is some sort of federal agreement on rapid deployment of renewable energy, or high-speed rail, or electric vehicle charging stations — it's increasingly difficult to have systems that in the aggregate will effect change," she says. Federal preemption, she acknowledges, should be a "drop-dead trump card" for moving projects forward. "But it's necessary when you have the evidence."

I didn't come up with the idea of giving the feds more authority to push through climate projects; it was actually on the table in the debt-limit deal that Congress passed in the spring. It didn't make it in. Nobody wants a transmission line running above their homes, and oil and gas money has no interest in making it easier to build them. To them I say, tough luck. Better to see a power line than not have a planet.

A new federal regulatory regime won't solve everything. For one thing, NECA couldn't fix every state and local rule that's standing in the way of progress. But it could preempt some of the ones that are the most absurdly obstructionist. Take housing, which is shaped mostly by zoning rules at the local level. NECA could prevent irate neighbors from saying no to new housing on environmental grounds, or from suing over ridiculous claims. That's how the feds used the Telecommunications Act to clear the way for cell towers. And that's what California just did when it passed a law explicitly barring opponents from using state environmental rules about "noise pollution" to block new housing, as they did at UC Berkeley and USC.

Look, I understand why the prospect of overhauling our hard-won environmental laws might feel like sacrilege to anyone who cares about the Earth. I myself grew up in a save-the-whales, no-nukes, recycle-your-aluminum-cans sort of home. But it was also a Star Trek house; I still think well-regulated technology can save the world.

And I'm far from a lone voice in the wilderness here. A few environmental big shots have come out swinging on the need for a new regulatory regime. Bill McKibben, a sort of patron saint of the environmental movement, wrote an article in Mother Jones earlier this year called "Yes in Our Backyards," calling for old-school tree huggers to embrace massive electrification infrastructure. "Maybe we could gaze up at wind turbines on the ridge and take pleasure in seeing the breeze made visible," McKibben writes. "And in seeing ourselves taking responsibility for something we need — energy — instead of pawning the costs off on poorer people somewhere else, or on the people who will come after us."

Late last year, the longtime environmental lawyer Michael Gerrard — faculty director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University — banged the same shoe on the same table. In an article called "A Time for Triage," he argued that the current crisis was great enough to put aside some old ecological bugbears. "There are some models of laws that have achieved speedy approvals for certain kinds of projects," he writes, citing the Telecommunications Act of 1996, among others. "Whatever it is, I believe we need to move forward in this fashion, and not just plod along with business-as-usual environmental regulation toward a world of killing heat and mass human migration and species extinction."

Matt Harrison Clough for Insider

Still, lots of Democrats and progressives find themselves split on this stuff, philosophically. The old environmentalists, the ones most likely to donate money to a cause or a political campaign, grew up in the preservationist tradition. "When you talk to people who are very involved in the environmental movement, things like high-speed rail aren't necessarily uncontroversial," says Coleman, the energy law professor. "On the left there's really two positions. One is, let's achieve this — we need to make it easier to build new infrastructure to have cleaner energy sources and cleaner options. And the other idea is, let's just use less energy."

Two things can be true! We should absolutely find ways to reduce our impact on the Earth and on one another. But we built our way into this problem, with our car-based economy and our determination to burn fossil fuels every time we want to toast a slice of bread. So I have to believe we can build our way out of it. And it makes no sense to allow local residents (most of them wealthy and white) to use environmental laws to block projects that will give other people (most of them poor and people of color) stuff like affordable housing and a way to get to work in the morning. Some state governments and environmental groups, in fact, are so fed up with all the environmental NIMBYism that they've stopped participating in lawsuits against new housing.

"We have strayed from the path of 'purity' on that," says David Pettit, a senior attorney in the climate and clean-energy program at the famously litigious Natural Resources Defense Council. "We feel that building housing is so important that some changes have to be made."

We can't let local residents (most of them wealthy and white) block projects that give other people (most of them poor and people of color) stuff like affordable housing.

The truth is, our entire framework of environmental regulation has always been kind of elitist. It was based from the start on a misguided idea of nature — a sense that the environment is some other, removed place that retains a sublime quality where people can encounter God, as long as nobody touches it. That view is fine for the people with the financial wherewithal and free time to journey there, preferably with glamping-quality gear. "Only when we had a middle class with leisure time to spend in the great outdoors was when we had legislative support to get NEPA," says Spence, the professor of energy law. "Mostly, it's a relatively wealthy persons' movement, and you see that in the composition of environmental organizations." It's long past time we uproot the racist and classist assumptions that underlie our modern environmental regulations. Demolishing the old rules would not only spur the rapid and widespread building we need to protect the planet — it would take into account the needs of everyone.

The good news is, revamping our environmental regulations will work. In some places, it already has. Look at what happened recently in New York. After nearly two decades of coastal communities fighting the construction of offshore wind farms, the state finally passed a law limiting the range of grounds for opposition. Now five wind projects are in the works. In Florida, meanwhile, the high-speed-rail company Brightline has built a mini-network of trains across the state, and it has another one in the works connecting Southern California to Las Vegas, simply by making use of existing, already-permitted rail lines. If we use our heads — as well as our existing infrastructure — we can find ways to build big.

And we don't have to worry that changing environmental regulations will open the door for a lot of dirty, planet-polluting industries. Sure, Republicans and their petrochemical allies would love to get more natural-gas pipelines into the pipeline. But the fact is, the economy will no longer support those kinds of projects. Coal power isn't coming back, solar and wind are cheaper than fossil fuels, and almost all the energy projects in the overstuffed queue to connect to the national grid are renewables rather than oil and gas. The war's over; now we just have to win the peace.

Matt Harrison Clough for Insider

Calling for an overhaul of environmental protections remains something of a political third rail. But on background, many policy wonks and policymakers I spoke with are quick to admit that the current system doesn't work. They know we need to change it. They just aren't sure we can muster the political will to make it happen, even though it's supported by Republicans and Democrats alike.

I'm not claiming it'll be easy. The idea that we can protect the environment while continuing to feed our seemingly insatiable consumerist appetites in some even-handed equitable fashion is as pie-eyed as a "Star Trek" episode. Every decision we make about the "environment" is also a statement about who gets what. When an environmental regulation determines where, or whether, a factory can be built, it becomes economic policy. When environmental laws allow the continued operation of petrochemical refineries in the poorest communities in the poorest states, but disallow the construction of wind turbines off the richest beaches in the richest states, it becomes social policy. When a permitting process determines who will have jobs, or whether a city vulnerable to killer heat waves can have consistent electrical power, it becomes a social and economic determinant.

"These are deep questions of democracy and the administrative state," says Zachary Liscow, a former chief economist at the Office of Management and Budget who now teaches at Yale Law School. "Any of these infrastructure projects are a combination of two things — technical things that are very hard for the public to understand, but also deeply political choices about balancing development versus the environment and weighing the interests of different communities. Where do we want to lodge that authority?"

Right now, the answer to those questions is being held hostage, for the most part, by local interest groups. That's who's deciding our future. The problem is too big to leave to every high-horse property owner who feels like tilting at windmills. Our solutions have to be big, too. Global warming and the global economy didn't merge environmental rules with economic policy; they were never separate to begin with. But pretending that they are, and that environmental regulations are only about protecting nature from human greed, is why we don't build big anymore. And if we don't change course, it's going to get us all killed.

Adam Rogers is a senior correspondent at Insider.

Read More

By: [email protected] (Adam Rogers)

Title: Make America Build Again

Sourced From: www.businessinsider.com/america-build-infrastructure-transportation-housing-regulation-environment-2023-11

Published Date: Thu, 16 Nov 2023 10:40:01 +0000

.png)