The Obama administration dismantled several key intelligence programs that once played a vital role in the fight against drug trafficking, gang violence, and organized crime. These programs integrated law enforcement data with public health metrics to create early warning systems for emerging threats.

Yet they were terminated, driven largely by political considerations and concerns that the data disproportionately reflected criminal activity in specific demographic groups.

Under Democrat administrations, uncomfortable truths, such as the disproportionate amount of crime, drug trafficking, gang activity, and smuggling committed by illegal aliens, Latinos, and other minority groups, are suppressed and dismissed as disinformation.

The National Drug Intelligence Center (NDIC), established by Congress in 1993 and placed under the Attorney General’s authority, served as the nation’s primary hub for strategic domestic counterdrug intelligence until President Obama shut it down in 2012. Based in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, the NDIC employed over 300 federal and contract personnel at its peak.

What made the center unique was its integration of law enforcement intelligence with data from drug treatment facilities, enabling a more comprehensive view of the national drug landscape.

NDIC fulfilled several critical functions. Its predictive analysis capabilities allowed it to forecast emerging drug trends, giving federal agencies time to prepare and respond proactively rather than reactively. Its Document and Media Exploitation (DOMEX) teams analyzed seized assets, financial records, communications, and other materials to produce detailed profiles of drug trafficking networks, helping law enforcement “make sense of everything they seized.”

NDIC also produced in-depth regional threat assessments, such as the 2008 Indian Country Drug Threat Assessment, which examined trafficking across Native American reservations. Additionally, the center played a vital role in inter-agency coordination, synthesizing intelligence from the DEA, FBI, ATF, U.S. Marshals, and state and local law enforcement into unified reports.

Despite its effectiveness, NDIC faced political pressure throughout its existence and was ultimately shut down in 2012 under President Obama.

The Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring (ADAM) program operated from 1997 to 2003, collecting vital data on drug use among individuals arrested for various offenses. Revived briefly as ADAM II from 2007 to 2014, the program combined interviews and urinalysis to track drug use patterns within the criminal population, offering a rare and valuable window into the link between substance abuse and criminal behavior.

Unlike general population surveys, ADAM focused exclusively on arrestees, delivering real-time intelligence on drug use among those actively engaged in criminal activity. It highlighted regional variations by operating across dozens of metropolitan areas, allowing law enforcement to identify geographic patterns and emerging threats. Interviews provided long-term behavioral context, while urinalysis delivered objective, verifiable data on recent drug use, eliminating the inaccuracies of self-reporting.

ADAM’s insights supported courts, correctional facilities, and treatment providers in shaping intervention strategies and drug policy. However, the program was shut down in 2004 due to funding cuts. Although ADAM II was launched in 2007, it covered only 10 counties compared to the original program’s 35+ sites and was ultimately discontinued in 2014, under President Obama, permanently ending a unique and irreplaceable source of intelligence on drug use in the criminal population.

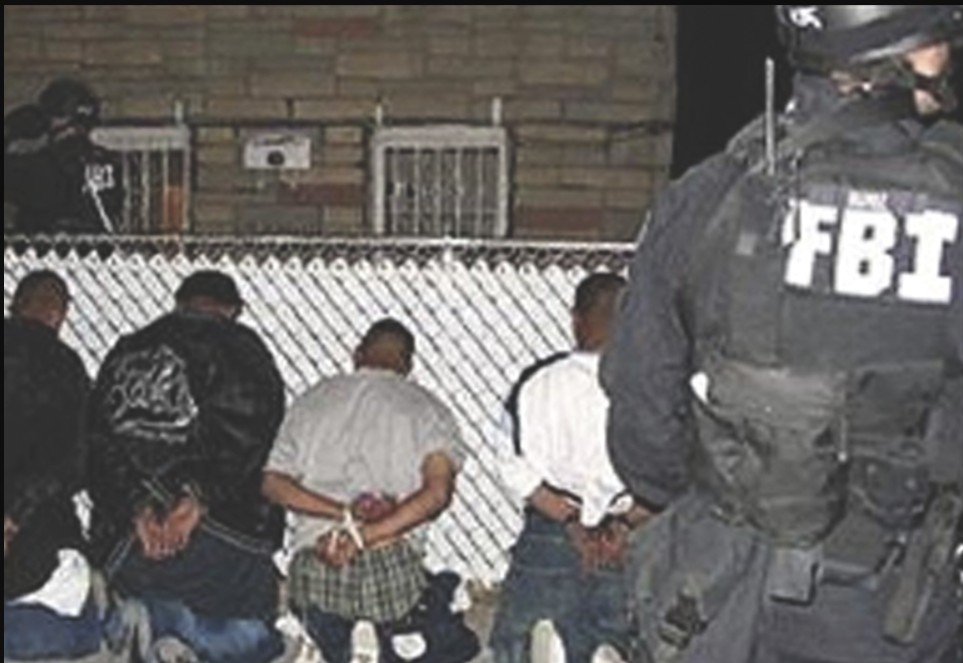

The FBI’s National Gang Threat Assessment, produced by the National Gang Intelligence Center (NGIC), provided detailed analysis of gang activity, membership trends, and emerging threats across the United States. These reports consolidated intelligence from federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies, making them a crucial tool for understanding the evolving gang landscape.

The 2011 assessment estimated that 1.4 million active gang members were operating within more than 33,000 gangs nationwide, data that played a key role in guiding law enforcement resource allocation. The reports also identified emerging threats, such as the rapid spread of Sureno gangs and the development of “hybrid gangs” with mixed affiliations.

Regional analyses allowed local agencies to contextualize their own gang problems within broader national trends, while additional reporting tracked how gangs adapted to new technologies, including the use of social media for recruitment and coordination.

Despite their strategic importance, these intelligence products were largely discontinued under President Obama. The FBI ceased publishing national gang membership estimates after 2009. The Department of Justice’s National Gang Center stopped reporting gang quantities and membership data in 2012.

That same year, the National Youth Gang Survey ended. The final Attorney General’s report to Congress on violent street gangs in suburban areas was issued in 2008. The termination of these programs left a significant gap in America’s ability to monitor and respond to gang-related threats on a national scale.

The termination of these intelligence programs resulted in the loss of critical institutional knowledge and long-term data continuity. Over 19 years, the NDIC had developed deep expertise in analyzing drug trafficking patterns and criminal networks, expertise that was scattered when the center closed. Former officials emphasized that NDIC’s core value was its objective analysis, which often exposed uncomfortable truths about failed drug policies.

As one former director noted, the center served as “a regular reminder that their policies were failing,” making it a political target. Without the NDIC and comprehensive gang intelligence reporting, law enforcement has been left struggling to keep up with increasingly sophisticated drug traffickers and tech-enabled gangs.

Similarly, the ADAM program’s longitudinal data allowed researchers and law enforcement to track drug use trends over time within criminal populations. Its termination disrupted that continuity, making it harder to detect emerging patterns.

The FBI’s gang assessments had offered a comprehensive national picture, enabling local agencies to understand how their challenges fit into wider trends. With these tools gone, law enforcement agencies have been left operating in the dark, lacking the strategic insight once provided by these coordinated efforts.

Recent legislative efforts have acknowledged the damage. In both 2021 and 2023, Senators Chuck Grassley and Jacky Rosen introduced the Gang Activity Reporting Act, which would require the Justice Department, Department of Homeland Security, and FBI to resume regular reporting on gang membership and criminal trends. “To best combat violent crime, Congress must have a clear picture of membership trends and activity of criminal gangs, who are responsible for nearly half of all violent crime.

Hopefully, with the Trump administration’s renewed crackdown on illegal immigration and its efforts to secure the southern border, these reporting and intelligence programs, or new ones like them, can be restored.

The post How Obama Dismantled America’s Drug, Crime, and Gang Intelligence Infrastructure appeared first on The Gateway Pundit.

------------Read More

By: Antonio Graceffo

Title: How Obama Dismantled America’s Drug, Crime, and Gang Intelligence Infrastructure

Sourced From: www.thegatewaypundit.com/2025/08/how-obama-dismantled-americas-drug-crime-gang-intelligence/

Published Date: Thu, 07 Aug 2025 12:00:42 +0000

.png)