A new book rounds up hundreds of unbuilt structures and city plans from the 20th century to today that show just how different our world could have looked.

We’ve lost countless historic and architecturally significant buildings over the course of human history, but there are even more that never made it past the drafting stage. As architecture writers Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin point out in their new Phaidon book Atlas Of Never Built Architecture (out May 22), buildings are a collection of ideas, stories, struggles, cultures, and circumstances, and they’re subject to all manner of delays, whims, and fads—as well as both economic and political pressures. An architect may draft up a masterpiece, but it may never come to fruition, or if it does, it might have to go through a government committee first, who Lubell and Goldin write, "smudge brilliant imagery into dulled down reality."

For Atlas Of Never Built Architecture, Goldin and Lubell made a shortlist of 5,000 unbuilt projects from the 20th and 21st centuries they felt were significant, then painstakingly whittled it down to 350 interesting, grand, and architecturally and historically significant projects to feature. The projects span the globe, from a Frank Lloyd Wright plan for Greater Baghdad to Walt Disney’s vision for a 20,000-person-strong planned community he claimed would help fix American cities. Below is just a small smattering of those unrealized structures the world never saw.

Kalevalatalo

The Kalevala House, or Kalevalatalo in Finnish, was designed in 1921 by Eliel Saarinen (father to Eero Saarinen), as a monument of sorts to Finnish cultural studies and nationalism. Set about three miles from the center of Helsinki, the building was meant to be absolutely massive, housing a museum, library, amphitheater, lecture hall, reading room, ballroom, workshops and galleries for artists, and a number of apartments, all surrounding a 16-sided, 262-foot-tall pantheon. Saarinen also wanted the building to sit on top of a crypt for great artists, once writing that he’d put "frescoes of the great masters and statues along the walls." Unfortunately for Saarinen and all those late artists, the group backing the project ran out of money, and one of the building’s biggest supporters, Finnish painter Akseli Gallen Kallela, also pulled out, saying the structure had "progressed too far into the sign of antiquity."

Boston Center Plan

After being recruited to work at Harvard following their exile from Nazi Germany, Walter Gropius and Martin Wagner (former colleagues at the Gropius-founded Bauhaus school) taught a 1942 seminar called The New Boston Center, in which students were tasked with reimagining the core of what was then a struggling city. From those germs, the two architects crafted their Boston Center Plan, which called for the large-scale demolition of the city’s outdated buildings and streets, as well as the construction of an arc-shaped megastructure lined with slabs and towers that held everything from hotels to helicopter terminals. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Boston residents didn’t exactly jump at the plan to tear down their city’s charming, historic buildings, and the design was shelved.

The Tour Paris-Montréal was intended to be the main attraction of Canada’s 1967 centennial celebrations, designed by the city of Montréal in collaboration with the city of Paris.

Courtesy of City of Montreal Archives, published in Atlas of Never Built Architecture (May, 2024)

Tour Paris-Montréal

Designed by the city of Montréal in collaboration with the city of Paris and intended to be the chief attraction of Expo 67 for Canada’s centennial celebrations, the Tour Paris-Montréal was a cantilevered concrete tower that was meant to sweep up over the city from its perch at the tip of Île Sainte-Hélène. From its peak, visitors could have seen over 50 miles in all directions, and experts said the building was "one of the best specimens of modern art for the next 30 or 50 years." Unfortunately, experts also said it would’ve cost $20 million to build—a figure that was eventually shown to be an underestimation, causing the city of Paris to drop out of the project. Montréal countered the move with a suggestion that Paris dismantle and send the Eiffel Tower to Canada for the expo instead—a notion that France’s then president Charles De Gaulle was apparently cool with—but other French officials balked, saying they’d only go for the idea if organizers could promise that they’d return all 18,038 pieces of metal, 2.5 million rivets, and 60 tons of paint perfectly intact.

Los Angeles International Airport (LAX)

Ask any Angeleno and they’ll tell you that LAX leaves a lot to be desired. But ah, what could have been! Originally designed by L.A. architecture firm Pereira & Luckman in 1952, the space-age glass dome would have enclosed a grand concourse for arrivals and departures, a floating restaurant designed by trailblazing Black architect (and Golden Age of Hollywood "starchitect") Paul R. Williams, plus all sorts of other terrazzo finishes and indoor greenery. Eventually the design would morph into what became a scaled-down version of the firm’s original vision: the 1961 LAX Theme Building, a landmark central feature in an otherwise frustratingly disjoined and outmoded airport.

Mile-High Tower

A singular design from a then 89-year-old Frank Lloyd Wright, the proposed tripod-shaped skyscraper was presented to the press in Chicago in 1956. Wright said the 528-story mixed-use tower would hold 100,000 occupants and 15,000 cars, becoming a sort of vertical city. It might seem preposterous now—528 stories? 100,000 people?—but Wright was pretty serious about the whole thing at the time. Designed to use his "tap root" technique, which buried a steel-reinforced concrete core deep in the ground, the tower’s individual floors were cantilevered via steel supports, "like the branches of a tree," Lubell and Goldin write. Wright never found a tenant or a site for the project, though, and he died just three years later.

EPCOT

Everyone knows about Epcot in Orlando, the Disney outshoot with the big golf ball–like Spaceship Earth at its core. What even the most devoted Disneyheads might not know, though, is that Walt Disney initially envisioned it as an acronym for the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow. A planned city of about 20,000 people, EPCOT would be car-free by virtue of a series of monorails and people movers, shuttling residents to the city’s offices, shops, restaurants, hotels, and green belt. The core of the development was to be covered in a clear dome to protect it from the elements—or keep them out altogether, really—and cars and buses supplying the city would be forced to drive under it, where a series of roads and loading docks would be constructed.

At the time, Disney said that EPCOT was "a living blueprint of the future," and "a showcase to the world for the ingenuity and imagination of American free enterprise." But unfortunately for America (maybe?) he died just two months after he presented the idea in 1966, and the company he once ran ended up deciding his big plan was just too risky.

A few years after plans for Zaha Hadid’s proposed Stone Towers in Cairo, Egypt, were unveiled in 2009, the company that commissioned her stopped backing the project.

Courtesy of Zaha Hadid, published in Atlas of Never Built Architecture (Phaidon, May 2024)

Stone Towers

Envisioned for Cairo’s Katameya suburb, Zaha Hadid’s proposed Stone Towers look like an absolutely massive undertaking. The 18 double-slap buildings would have been spread over a roughly four-acre plaza, holding a five-star hotel, about 1,430 residential units, and more than 30 million square feet of office space. The plans for the buildings’ curved faces evoked a reflection rippling in a mirror or on water, and the dashes cut into the precast concrete were meant to mimic ancient Egyptian carvings. Unfortunately for Hadid’s vision, the company that commissioned her—the Rooya Group—stopped backing the project a few years after the design’s 2009 unveiling, choosing to construct a fairly conventional pseudo-Mediterranean complex on the site instead.

Machu Picchu Hotel

Designed by Peruvian modernist Miguel Rodrigo Mazuré in 1969, the Machu Picchu Hotel, Goldin and Lubell write, would have "hovered over the Andes like a condor god frozen in concrete"—if it had ever come to fruition. The multiwinged, sci-fi-inspired design featured sloping windows on the undersides of its hallways (or tubes, as Mazuré called them), as well as an enormous rooftop deck with a pool. But set adjacent to the 15th-century Inca citadel, the hotel would have looked anomalous at best, considering it brought absolutely nothing from its namesake into its design. That being said, following a 1968 coup d’état in Peru, these kinds of monumental concrete buildings were seen as a sort of homage to the country’s precolonial past, the modern equivalent of the mud-and-stone buildings that made up much of the Inca world. "Nationalism," Lubell and Goldin write "is the stock-in-trade of military regimes, but why Mazuré’s tourist hotel wasn’t among its built representations is now lost to time."

Mansion House Square

A shockingly out-of-place structure designed by Mies van der Rohe in 1962, Mansion House Square was intended to be set in the center of London. Stark and serene in its boxy steel frame, the building looked quite a lot like the architect’s famous Seagrams Building in New York, though it would be clad in bronze, with amber-colored windows. At 19 stories, it would have towered over much of the nearby landscape, though, and it quickly became a point of contention in the British government, with King Charles III (then Prince Of Wales) reportedly calling it "a giant glass stump better suited to downtown Chicago." The building underwent about two decades of planning reviews before falling victim to Margaret Thatcher’s conservative government, who thought that the way it was set back from the street, creating a natural plaza for people to gather, would have invited too much civil disobedience.

Centre Pompidou

Centre Pompidou, with its inside-out design and striking escalators, is a Parisian classic. And yet, what could have sat there was even wilder, with French architect André Bruyère entering a rather colossal egg-like structure into the 1969 competition for the commission. Standing about 344 feet tall on three legs and covered in thousands of six-and-a-half-foot scales made out of glass, concrete, or alabaster, L’Oeuf was more of a wild idea than an actual building plan. A monorail was meant to enter the egg at one side, circling through the entire structure like a long ribbon, and the foyer was designed to sit inside a floating glass globe, like a yolk. It wasn’t exactly practical, to say the least, and ultimately Bruyère lost the competition to Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano.

Obus E. Office Tower

Le Corbusier designed a number of megascale master plans throughout his career, including ones for Paris, Rio de Janeiro, and Casablanca. Goldin and Lubell contend that most of them recommended that whatever colonial government was in place rip out all existing indigenous structures and culture, instead creating what the pair call "a modern utopia ruled by science and order." Corbusier designed plan after plan for what he thought should happen in Algeria, with his most fleshed out one, Plan Obus. Released in 1938, the design advocated for a giant bridge stretching over the city’s Casbah quarter, a new business district on the Cape of Algiers, and an elevated highway containing 14 residential levels beneath its roadway. The plan was rejected unanimously by the local council in Algiers, who said "it is not desirable to attempt such a random experiment on such a considerable perimeter."

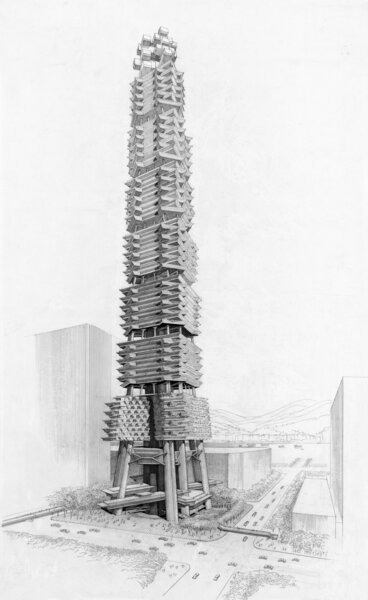

A sketch of architect Paul Rudolph’s planned Sino Tower in Hong Kong, designed in 1989.

Courtesy of Paul Rudolph Institute / Library of Congress, published in Atlas of Never Built Architecture (May, 2024)

See the full story on Dwell.com: 12 Architectural Masterpieces That Never Were

Related stories:

- Deck Chairs, Tuberculosis, and the Titanic: The Unexpected Origins of a Summertime Staple

- Are We Heading for Another Attempted Waterbed Revival?

- A Timeline of Sonja Morgan’s Many, Many Attempts to Sell Her New York City Townhouse

Read More

By: Marah Eakin

Title: 12 Architectural Masterpieces That Never Were

Sourced From: www.dwell.com/article/atlas-of-never-built-architecture-phaidon-unbuilt-structures-and-city-plans-0e50c6ed-e6641435

Published Date: Wed, 22 May 2024 17:33:53 GMT

.png)