The transparent material has long been a go-to for modern architects who want to make a statement. Surprisingly, it was as provocative in 2002 as it was in 1931.

As a part of our 25th-anniversary celebration, we’re republishing formative magazine stories from before our website launched. This story previously appeared in Dwell’s August 2002 issue.

1931: The Maison de Verre, Paris, Pierre Chareau and Bernard Bijovet

Shoehorned into a Left Bank courtyard, this small building was designed to house a doctor’s office and an upstairs apartment. The walls are made of translucent glass brick supported by a steel frame. Unlike later glass houses, this one reveals little of the life within. This first glass house is nothing but a tease.

1934: The Crystal House at the Century of Progress Exhibition, Chicago, Illinois, George and William Keck

One of 13 model homes built along Lake Michigan, this World’s Fair House of Tomorrow by the brothers Keck pointed the way to the near future. Its ground floor was clad in translucent rippled glass for privacy. Tinted glass was used for the middle floor, and clear glass was used on the top floor. A Buckminster Fuller Dymaxion car was parked in the garage.

1947-48: The Dover Sun House, Dover, Massachusetts, Maria Telkes and Eleanor Raymond

The "Sun Queen," Hungary-born scientist Dr. Maria Telkes, who later designed a solar oven, combined forces with New England architect Eleanor Raymond to build the first house to intentionally harness solar power. The house derived 80 percent of its heat from the sun and Telkes attempted to use Glauber’s salt to store the sun’s energy.

1959-60: Case Study House #22, Los Angeles, California, Pierre Koenig

The breathtakingly minimalistic design of the home built for Buck and Carlotta Stahl (who still own it) was made famous by the Julius Shulman photo of the girls in white dresses, floating like astronauts above the Hollywood Hills. Constructed of 20-foot-wide sheets of glass held in place by a steel frame, outfitted with compact, freestanding kitchen modules and a walk-around fireplace, this Case Study House was crafted specifically to immerse the occupants in the magnificent view.

1981: The Glass and Steel House, Chicago, Illinois, Krueck & Sexton

A Miesian box built at a moment when high modernism was out of favor: "I had left architecture because of postmodernism," recalls architect Ronald Krueck. "Then I met this individual who was interested in this other aesthetic that was not popular at the time." The client wanted "a factory on the outside and Milan 1970 on the inside." The resulting 5,000-square-foot, two-story house, located on Chicago’s Near North Side, is a simple rectangle set way back from the street, discreetly hidden behind a brick garden wall.

1984: Benthem House, Almere, the Netherlands, Benthem Crouwel Architects

A glass box sitting atop a space frame, this house was designed for an "unusual homes" competition in which architects were instructed to design without taking current building regulations into account. The architects pioneered the use of glass as a load-bearing material; the floor-to-ceiling sheets of glass support the corrugated steel roof.

Photos by Evelyn Hofer (1931), Hedrich-Blessing/Chicago Historical Society (1934), Courtesy of the Maria Telkes Collection, Special Collections Architecture & Environmental Design Library/Arizona State University (1947-48), Julius Shulman (1959-60), Bill Hedrich/Hedrich-Blessing (1981), Michael Claus (1984)

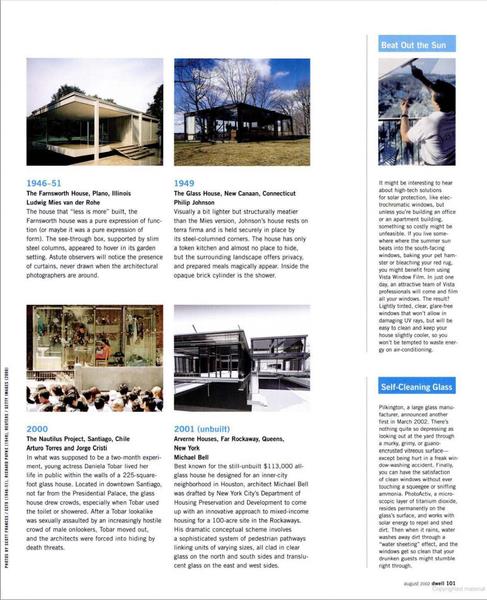

1946-51: The Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

The house that "less is more" built, the Farnsworth House was a pure expression of function (or maybe it was a pure expression of form). The see-through box, supported by slim steel columns, appeared to hover in its garden setting. Astute observers will notice the presence of curtains, never drawn when the architectural photographers are around.

1949: The Glass House, New Canaan, Connecticut, Philip Johnson

Visually a bit lighter but structurally meatier than the Mies version, Johnson’s house rests on terra firma and is held securely in place by its steel-columned corners. The house has only a token kitchen and almost no place to hide, but the surrounding landscape offers privacy, and prepared meals magically appear. Inside the opaque brick cylinder is the shower.

2000: The Nautilus Project, Santiago, Chile, Arturo Torres and Jorge Cristi

In what was supposed to be a two-month experiment, young actress Daniela Tobar lived her life in public within the walls of a 225-square-foot glass house. Located in downtown Santiago, not far from the Presidential Palace, the glass house drew crowds, especially when Tobar used the toilet or showered. After a Tobar look-alike was sexually assaulted by an increasingly hostile crowd of male onlookers, Tobar moved out, and the architects were forced into hiding by death threats.

2001 (unbuilt): Arverne Houses, Far Rockaway, Queens, New York, Michael Bell

Best known for the still-unbuilt $113,000 all-glass house he designed for an inner-city neighborhood in Houston, architect Michael Bell was drafted by New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development to come up with an innovative approach to mixed-income housing for a 100-acre site in the Rockaways. His dramatic conceptual scheme involves a sophisticated system of pedestrian pathways linking units of varying sizes, all clad in clear glass on the north and south sides and translucent glass on the east and west sides.

Photos by Scott Frances/Esto (1946-51), Richard Payne (1949), Reuters/Getty Images (2000)

See more from the Dwell archive on US Modernist.

Related Reading:

The Case Against Glass Houses

From the Archive: Philip Johnson’s Glass House Gets a Restoration

Read More

By: Dwell Staff

Title: From the Archive: A Brief History of the Glass House

Sourced From: www.dwell.com/article/from-the-archive-tk-tk-80e20aec

Published Date: Thu, 02 Oct 2025 16:49:18 GMT

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginbusiness.business/real-estate/flush-with-original-finishes-this-socal-midcentury-lists-for-2m

.png)