Before "aging in place" was a widely known concept, Michael Hughes built his parents a house for retirement that demonstrated a new kind of frankness around long-term planning.

As a part of our 25th-anniversary celebration, we’re republishing formative magazine stories from before our website launched. This story previously appeared in Dwell’s February 2001 issue.

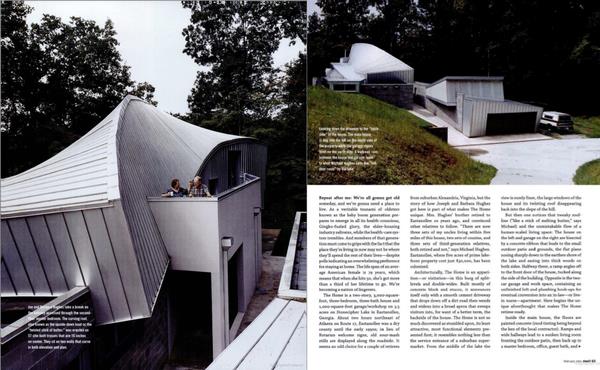

Repeat after me: We’re all gonna get old someday, and we’re gonna need a place to live. As a veritable tsunami of oldsters known as the baby boom generation prepares to emerge in all its health-conscious, Gingko-fueled glory, the elder-housing industry salivates, while the health-care system trembles. And members of that generation must come to grips with the fact that the place they’re living in now may not be where they’ll spend the rest of their lives—despite polls indicating an overwhelming preference for staying at home. The lifespan of an average American female is 79 years, which means that when she hits 50, she’s got more than a third of her lifetime to go. We’re becoming a nation of lingerers.

The Home is a two-story, 3,000-square-foot, three-bedroom, three-bath house and 1,000-square-foot garage/workshop on 3.5 acres on Stonecipher Lake in Eastanollee, Georgia. About two hours northeast of Atlanta on Route 17, Eastanollee was a dry county until the early 1990s; in lieu of Rotarian welcome signs, old sour-mash stills are displayed along the roadside. It seems an odd choice for a couple of retirees from suburban Alexandria, Virginia, but the story of how Joseph and Barbara Hughes got here is part of what makes The Home unique. Mrs. Hughes’s brother retired to Eastanollee 10 years ago, and convinced other relatives to follow. "There are now three sets of my uncles living within five miles of this house, two sets of cousins, and three sets of third-generation relatives, both retired and not," says Michael Hughes. Eastanollee, where five acres of prime lakefront property cost just $30,000, has been colonized.

Photo: Alex Harris

Architecturally, The Home is an apparition—or visitation—in this burg of split-levels and double-wides. Built mostly of concrete block and stucco, it announces itself only with a smooth cement driveway that drops down off a dirt road then wends and widens into a broad apron that sweeps visitors into, for want of a better term, the backside of the house. The Home is not so much discovered as stumbled upon, its least attractive, most functional elements presented first; it resembles nothing less than the service entrance of a suburban supermarket. From the middle of the lake the view is surely finer, the large windows of the house and its twisting roof disappearing back into the slope of the hill.

But then one notices that tweaky roofline ("like a stick of melting butter," says Michael) and the unmistakable flow of a human-scaled living space: The house on the left and garage on the right are bisected by a concrete ribbon that leads to the small outdoor patio and grounds, the flat plane nosing sharply down to the earthen shore of the lake and easing into thick woods on both sides. Halfway there, a ramp angles off to the front door of the house, tucked along the side of the building. Opposite is the two-car garage and workspace, containing an unfinished loft and plumbing hookups for eventual conversion into an in-law—or live-in nurse—apartment. Here begins the unique forethought that makes The Home retiree-ready.

Photo: Alex Harris

Inside the main house, the floors are painted concrete (mod tinting being beyond the ken of the local contractor). Ramps and wide hallways lead to a sunken living room fronting the outdoor patio, then back up to a primary bedroom, office, guest bath, and primary bath with a whirlpool tub and roll-in shower. A laundry room is conveniently close to the bedroom. All doorways are a wheelchair-friendly 36 inches wide. The only part of the first floor not handicap-accessible is a small eating area off the kitchen, with its own lake view—either a refuge from rolling oldies or a matter of practicality, because ramps need room to rise. Upstairs is another large bedroom and bath, plus "attic" storage located beyond an unassuming door at the end of the hall—no stairs required. The upstairs bedroom contains one of The Home’s strongest features, a huge window that juts out from the front of the house. Michael says he made sure the view up here was better than in the living room, to encourage his parents to climb up and down for as long as they are able.

Overall, The Home feels like a custom-built house by someone enamored of Gehryesque industrial materials, with soaring walls, a floating staircase, and a bridge instead of an enclosed upstairs hallway—pretty standard stuff, really, part of the repertoire of any big-city architect. (Indeed, Michael was an intern in the offices of both Frank Gehry and Richard Meier.) From its cardboard-gray color to the lack of landscaping, The Home looks like an architect’s maquette plopped into the Georgia woods. But it’s toady with a purpose: Paramount are low maintenance and low cost, major concerns for retirees on a fixed income. The Home could’ve been clad in redwood, the better to ease its geometric shapes into the landscape. But wood requires upkeep—stain, paint, replacement—and thus both money and effort. Michael built The Home on a budget of about $250,000, all materials, land, and labor included, the latter provided mainly by himself and his relatives and friends. (A local contractor quoted a price of $350,000 for the whole thing—more if he wanted it in writing.) Only the concrete work and roofing were tackled by professionals, and all materials were purchased from local suppliers. Interior fixtures were either bought cheap at the local Home Depot or made (or are yet to be made) by Michael and his father.

Photo: Alex Harris

See the full story on Dwell.com: From the Archive: An Architect Designs "Not Your Average Old-Folks Home, for Better and Worse"

Related stories:

- Completely Knocking Down the Original Scottish Stone Cottage Would Have Been Easier

- A Hamptons Beach Bungalow, But Make It Sea Ranch

- Dwell Open House 2025: 350 Readers Tour Some of L.A.’s Most Unforgettable Homes

Read More

By: David A. Greene

Title: From the Archive: An Architect Designs "Not Your Average Old-Folks Home, for Better and Worse"

Sourced From: www.dwell.com/article/from-the-archive-michael-hughes-retirement-the-home-aging-in-place-aaea5e93-e02ab56c

Published Date: Thu, 20 Nov 2025 14:36:50 GMT

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginbusiness.business/real-estate/how-they-pulled-it-off-a-107squarefoot-parisian-studio-inspired-by-midcentury-ships

.png)