Though it’s since been relocated, the drama surrounding the 1980s Winton Guest House raised questions about preserving architecture—and who gets to save it.

As a part of our 25th-anniversary celebration, we’re republishing formative magazine stories from before our website launched. This story previously appeared in Dwell’s April/May 2004 issue.

Should someone want to paint dogs playing poker over a Picasso, a Mondrian, or a Miró, most people would protest the act as the desecration of great art—and mock the hubris of the re-painter. But when a contemporary architectural icon is under threat of destruction, many people still shrug their shoulders and step calmly aside. The current controversy (or, rather, lack thereof) over Frank Gehry’s Winton Guest House in Wayzata, Minnesota—which many consider to mark the beginning of Gehry’s rise to international acclaim—is a textbook case of the preservation uncertainties faced by so many examples of fine architecture today.

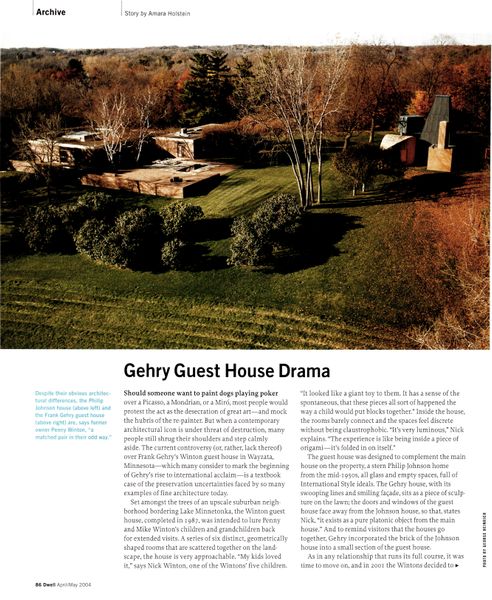

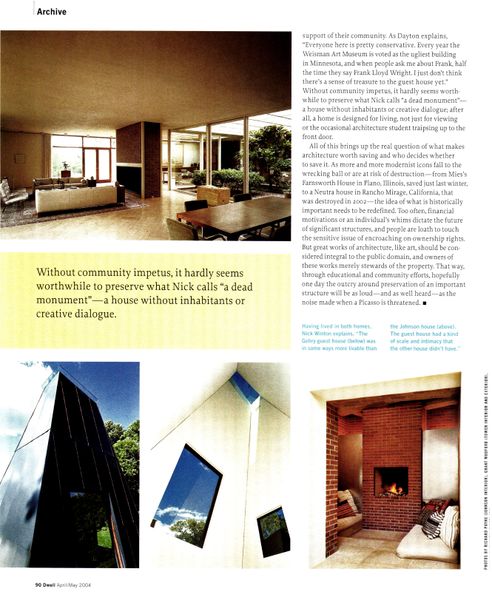

Set amongst the trees of an upscale suburban neighborhood bordering Lake Minnetonka, the Winton Guest House, completed in 1987, was intended to lure Penny and Mike Winton’s children and grandchildren back for extended visits. A series of six distinct, geometrically shaped rooms that are scattered together on the landscape, the house is very approachable. "My kids loved it," says Nick Winton, one of the Wintons’ five children. "It looked like a giant toy to them. It has a sense of the spontaneous, that these pieces all sort of happened the way a child would put blocks together." Inside the house, the rooms barely connect and the spaces feel discrete without being claustrophobic. "It’s very luminous," Nick explains. "The experience is like being inside a piece of origami—it’s folded in on itself."

The guest house was designed to complement the main house on the property, a stern Philip Johnson home from the mid-1950s, all glass and empty spaces, full of International Style ideals. The Gehry house, with its swooping lines and smiling facade, sits as a piece of sculpture on the lawn; the doors and windows of the guest house face away from the Johnson house, so that, states Nick, "it exists as a pure platonic object from the main house." And to remind visitors that the houses go together, Gehry incorporated the brick of the Johnson house into a small section of the guest house.

Photo: George Heinrich

As in any relationship that runs its full course, it was time to move on, and in 2001 the Wintons decided to sell the house: "In some ways, my parents wanted to get out from underneath the baggage that came with owning an icon," says Nick. His parents’ new, more manageable home is a loft in downtown Minneapolis designed by Nick, a partner at Anmahian Winton Architects in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The 11-acre property on which the Gehry and Johnson houses both sit was sold to Kirt Woodhouse, a local developer, who divided the property into three parcels— assigning each house to a separate site, and then a third, empty lot. The Johnson house was bought in 2002 by a retired couple, but the Gehry house is still unsold, hence the crux of the current problem.

In America—where individual needs usually take precedence over artistic ideals—it’s still the right of the owner to dispose of a house. Fortunately, Woodhouse frankly states, "The last thing I would want to do is destroy the house," and he has even offered to donate the guest house—sans land—to a willing nonprofit organization. An independent art school, the Minnetonka Center for the Arts, has mulled over the idea of moving the house to its site less than a mile away, to use as housing for its artists in residence.

In November 2003, the center’s architect, James Dayton, of James Dayton Design in Minneapolis, brought Gehry—in whose office he worked for five years—into the mix. "We had talked about Frank redesigning the site at the arts center, and giving the guest house a new site-specific setting. It was conceived of as a piece of sculpture, and there are many good examples of artwork that are transferred from people’s houses into museums, where the intellectual value of that artwork isn’t compromised by being in a different setting. Understanding that it’s not as pure artistically, I think there’s something nice about opening it up to the world and keeping it around for other generations to experience."

Others have been vocal about the importance of keeping the structure at its original site, arguing that the context itself is integral to the architecture—and that removing it from the site irreparably damages its artistic integrity. Suzanne Ritus, an industrial designer who is now renting the guest house, says, "Gehry created a dialogue between the two structures that really involves the observer. It’s a dialogue that would be lost forever should the Gehry house be moved." Ritus has started a nonprofit, Foundations of Modern Architecture Inc., to keep the guest house in place—and should she succeed in raising the $1.7 million necessary to secure the property, she would open the site to architects, students, and builders to study and enjoy.

Photos by George Heinrich (Johnson), Mark Darley/Esto (Gehry)

But the issues at hand are larger than just "keep it or not." For one thing, as Nick notes, "houses that get landmarked need the cultural support of the area around them," and modern houses don’t always have the support of their community. As Dayton explains, "Everyone here is pretty conservative. Every year the Weisman Art Museum is voted as the ugliest building in Minnesota, and when people ask me about Frank, half the time they say Frank Lloyd Wright. I just don’t think there’s a sense of treasure to the guest house yet." Without community impetus, it hardly seems worthwhile to preserve what Nick calls "a dead monument"—a house without inhabitants or creative dialogue; after all, a home is designed for living, not just for viewing or the occasional architecture student traipsing up to the front door.

All of this brings up the real question of what makes architecture worth saving and who decides whether to save it. As more and more modernist icons fall to the wrecking ball or are at risk of destruction—from Mies’s Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois, saved just last winter, to a Neutra house in Rancho Mirage, California, that was destroyed in 2002—the idea of what is historically important needs to be redefined. Too often, financial motivations or an individual’s whims dictate the future of significant structures, and people are loath to touch the sensitive issue of encroaching on ownership rights. But great works of architecture, like art, should be considered integral to the public domain, and owners of these works merely stewards of the property. That way, through educational and community efforts, hopefully one day the outcry around preservation of an important structure will be as loud—and as well heard—as the noise made when a Picasso is threatened.

Photos by Richard Payne (Johnson Interior), Grant Mudford (tower interior and exterior)

See the full story on Dwell.com: From the Archive: The Fight Over an Early Frank Gehry Masterpiece

Related stories:

- From the Archive: Inside London’s Pioneering Prefab Housing Complex

- From the Archive: Wait, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Son Invented Lincoln Logs?

- From the Archive: The Problem With Building Up Boomtowns

Read More

By: Amara Holstein

Title: From the Archive: The Fight Over an Early Frank Gehry Masterpiece

Sourced From: www.dwell.com/article/from-the-archive-the-fight-over-an-early-frank-gehry-masterpiece-92277549

Published Date: Thu, 17 Jul 2025 17:35:28 GMT

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginbusiness.business/real-estate/in-norway-a-celebrated-artist-adds-a-creative-space-to-the-backyard-of-her-childhood-home

.png)