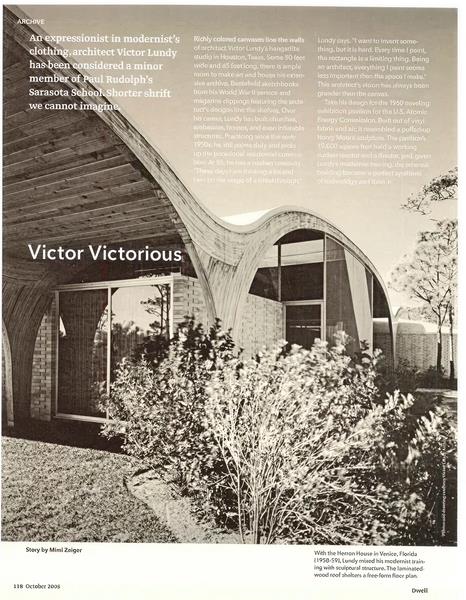

One considered a minor member of Paul Rudolph’s Sarasota School, Victor Lundy’s imaginative houses, churches, pavilions, and even paintings far exceeded his unwarrantedly low profile.

As a part of our 25th-anniversary celebration, we’re republishing formative magazine stories from before our website launched. This story previously appeared in Dwell’s October 2008 issue.

Richly colored canvases line the walls of architect Victor Lundy’s hangar-like studio in Houston, Texas. Some 50 feet wide and 65 feet long, there is ample room to make art and house his extensive archive. Battlefield sketchbooks from his World War Il service and magazine clippings featuring the architect’s designs line the shelves. Over his career, Lundy has built churches, embassies, houses, and even inflatable structures. Practicing since the early 1950s, he still paints daily and picks up the occasional residential commissions. At 85, he has a restless creativity. "These days I am thinking a lot and I am on the verge of a breakthrough," Lundy says. "I want to invent something, but it is hard. Every time I paint, the rectangle is a limiting thing. Being an architect, everything I paint seems less important than the space I make." This architect’s vision has always been grander than the canvas.

Take his design for the 1960 traveling exhibition pavilion for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. Built out of vinyl fabric and air, it resembled a puffed-up Henry Moore sculpture. The pavilion’s 19,000 square feet held a working nuclear reactor and a theater, and, given Lundy’s modernist training, the ethereal building became a perfect synthesis of technology and form.

Photos and drawings courtesy Victor Lundy Archive

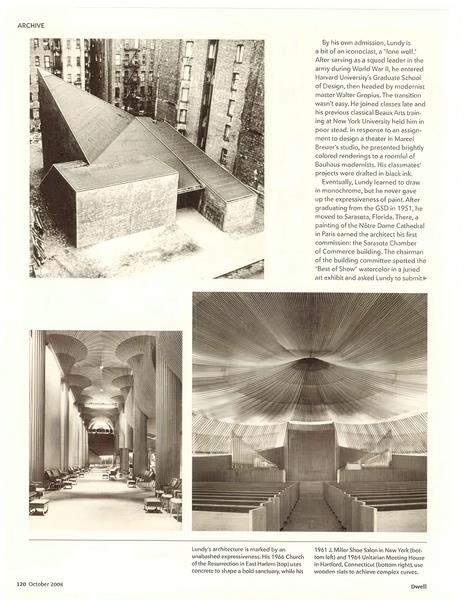

By his own admission, Lundy is a bit of an iconoclast, a "lone wolf." After serving as a squad leader in the army during World War Il, he entered Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, then headed by modernist master Walter Gropius. The transition wasn’t easy. He joined classes late and his previous classical Beaux Arts training at New York University held him in poor stead. In response to an assignment to design a theater in Marcel Breuer’s studio, he presented brightly colored renderings to a roomful of Bauhaus modernists. His classmates’ projects were drafted in black ink.

Eventually, Lundy learned to draw in monochrome, but he never gave up the expressiveness of paint. After graduating from the GSD in 1951, he moved to Sarasota, Florida. There, a painting of the Nôtre Dame Cathedral in Paris earned the architect his first commission: the Sarasota Chamber of Commerce building. The chairman of the building committee spotted the "Best of Show" watercolor in a juried art exhibit and asked Lundy to submit a scheme. The architect took his brushes to the site and dashed off a series of paintings that eventually became the design—his gestural stroke of celadon green became the tile roof.

Photos and drawings courtesy Victor Lundy Archive

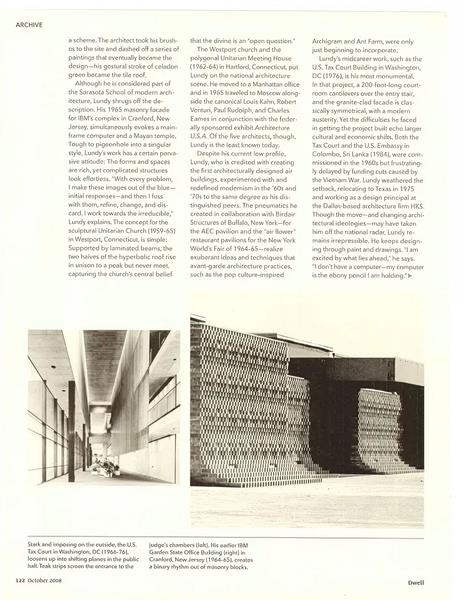

Although he is considered part of the Sarasota School of modern architecture, Lundy shrugs off the description. His 1965 masonry facade for IBM’s complex in Cranford, New Jersey, simultaneously evokes a mainframe computer and a Mayan temple. Tough to pigeonhole into a singular style, Lundy’s work has a certain pervasive attitude. The forms and spaces are rich, yet complicated structures look effortless. "With every problem, I make these images out of the blue—initial responses—and then I fuss with them, refine, change, and discard. I work towards the irreducible," Lundy explains. The concept for the sculptural Unitarian Church (1959-65) in Westport, Connecticut, is simple: Supported by laminated beams, the two halves of the hyperbolic roof rise in unison to a peak but never meet, capturing the church’s central belief that the divine is an "open question."

The Westport church and the polygonal Unitarian Meeting House (1962-64) in Hartford, Connecticut, put Lundy on the national architecture scene. He moved to a Manhattan office and in 1965 traveled to Moscow alongside the canonical Louis Kahn, Robert Venturi, Paul Rudolph, and Charles Eames in conjunction with the federally sponsored exhibit Architecture U.S.A. Of the five architects, though, Lundy is the least known today.

Photos and drawings courtesy Victor Lundy Archive

See the full story on Dwell.com: From the Archive: The Lesser-Known, "Lone Wolf" Modernist Master You Should Know

Related stories:

- These Tiny DIY Furniture Kits Inspire a Woodworker’s Life-Size Creations

- The Curators and Dealers Making the Next Generation of Design Stars in America

- Meet the Recipient of the First Frank Lloyd Wright Endowed Professorship

Read More

By: Mimi Zeiger

Title: From the Archive: The Lesser-Known, "Lone Wolf" Modernist Master You Should Know

Sourced From: www.dwell.com/article/from-the-archive-victor-lundy-modernist-biography-7c12eeee-d1fac664

Published Date: Thu, 27 Nov 2025 13:02:19 GMT

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginbusiness.business/real-estate/the-garage-was-in-bad-shape-so-she-swapped-it-out-for-a-crisp-art-studio

.png)