For years, policymakers and analysts have debated the reasons behind America’s worsening housing affordability crisis.

Some point to zoning and land-use restrictions, others to construction bottlenecks or rising interest rates. But a growing body of research suggests a deeper, structural problem; wages simply haven’t kept up with the cost of living.

That disconnect — according to two experts who study housing and labor markets — may hold the key to understanding why the American dream of homeownership is slipping out of reach.

Carter C. Price, senior mathematician at RAND Corp. and professor of policy analysis at the RAND School of Public Policy, recently authored a study showing that workers now receive a much smaller share of U.S. GDP than they did in the mid-20th century.

Laurel Kilgour, an attorney and research manager at the American Economic Liberties Project, told HousingWire that corporate consolidation and financialization continue to play a large role in reshaping housing, wages and market power.

Together, their findings suggest the affordability crisis isn’t just about the cost of homes — it’s about who’s getting paid, how much and who controls the flow of capital in the housing market.

Lost income, lost opportunity

Price’s research traces a sharp decline in the share of national income paid to the bottom 90% of workers.

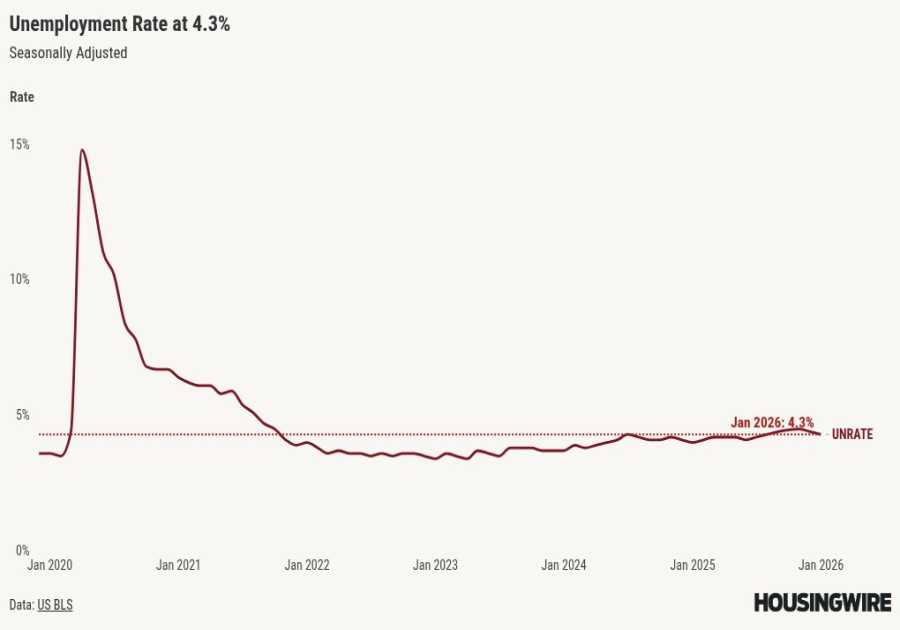

“We hadn’t seen the share of income going to the bottom 90% substantively increase up to 2019,” he said. “Inflation has been a lot higher, and while there has been slightly faster wage growth recently, that’s not going to make up for five decades of losses.”

His analysis found that America’s growing income inequality has carried an enormous cost for working households.

If the U.S. had maintained the same distribution of income that existed in 1975, the bottom 90% of earners would have collectively taken home about $3.9 trillion more in 2023 alone. When measured over the entire period from 1975 through 2023, that shortfall adds up to an astounding $79 trillion in lost income, the study found.

His team calculated that if income distribution had remained at 1970s levels, the median American household would have earned about $29,000 more in 2018 — and that lost income has likely increased in the years since.

Price explained that the loss in earnings directly translates to lost opportunities for homeownership.

“If they only save $20,000 of that extra $30,000, that’s a down payment on a $100,000 property,” he said. “That gets your 20% down. And if you save two years, that would be a down payment on a $200,000 property.”

Price said that even when mortgage rates drop, stagnant wages keep many households locked out of ownership.

From local lending to Wall Street

Kilgour sees a parallel story unfolding in the structure of housing finance.

She said decades of consolidation and deregulation have eroded the community-based lending networks that once financed smaller homebuilders.

“We used to have a system where the way that we supported local home building was through decentralized financial institutions,” Kilgour said. “We had a bunch of savings and loans institutions, and through bad policy choices, those all collapsed.”

As commercial banks merged and grew, Kilgour said they became less interested in serving local builders.

“When you have bigger banks, they have a bias towards lending to bigger clients and not doing that local lending as much,” she said. “The bigger banks are not filling that gap in local lending — and so it’s gotten harder and harder for smaller homebuilders to get the capital necessary to compete.”

That shift forced even large homebuilders to change how they operate.

“They went public in order to get access to capital, because that was essentially the only choice they had,” she said. “When they went public in the 1990s, that’s when those markets were starting to be subject to the shareholder primacy ideology.

“They have these incentives to sort of act on Wall Street’s demand for inventory discipline. That’s manifesting in many ways, including land banking. The larger homebuilders are getting more and more control of land. That means it’s harder for smaller homebuilders to build.”

When stagnant wages meet housing financialization

Both experts point to financialization — the growing dominance of financial markets and motives — as a common thread connecting stagnant wages and often insurmountable housing costs.

“There are a number of different things that are going on,” Kilgour said. “There’s financialization and a concentration angle in terms of monopsony (a market situation where there is only a single buyer for a good or service). If you have fewer employers to choose from, they’re not competing to pay you higher wages.”

Trade policy and job offshoring, she added, have compounded the problem.

“Our trade policies around offshoring jobs also have an impact on wages,” she said. “So there are a number of different things, but concentration is part of that.”

Price’s data aligns with that argument — showing that the U.S. economy continues to generate strong profits even as labor’s share declines.

“If you look at the median income growth, it was slightly higher in urban areas compared to suburban and rural,” he said. “At the top of the distribution, because of what we refer to as gentrification, high earners disproportionately moved into urban areas over the last 50 years, and that has seen the top of the income distribution grow much faster in urban areas.”

That uneven wage growth has pushed home prices in major metros far beyond reach for middle-income buyers.

“In urban areas with their high-paying jobs, those [house prices] have skyrocketed again,” Price said.

Build-to-rent, institutional ownership

Kilgour touched on investor homebuying and neighborhoods built specifically for rental purposes.

“That’s definitely something that within the past few years is having an impact,” she said. “In particular regions, they are buying up entire neighborhoods and basically saying families can’t buy anything in this area to own their own homes, it’s now just for rentals. It’s definitely something that is going to have more and more impact in the market going forward if policymakers don’t do anything about that.”

Price agreed that such patterns reflect deeper economic distortions.

“If you’re building to the market, and that middle part of the market has more money, then you would expect there to be more housing designed for that segment of the population,” he said. “If worker wages had kept pace with the overall economy, the housing landscape today would likely look very different.

“I think you’d see significantly fewer luxury condos and significantly more single-family homes.”

Kilgour also sees health care costs as a silent drag on wages.

“There is a significant portion of wages that is being suppressed through healthcare expenses, because our healthcare system is expensive and extracts a lot of money compared to other countries,” she said. “That’s something that both employers and employees would like to see addressed.”

A nation of renters

Looking ahead, Kilgour warned that the U.S. could face a profound political and social shift if homeownership continues to decline.

“I think the big story is changing from a nation of homeowners to a nation of renters,” she said. “People have lost sight of what that means politically. There used to be a bipartisan understanding about the importance of homeownership in America.”

Kilgour said those sentiments reflected a once-common belief that widespread ownership created civic harmony and shared prosperity.

“Certain portions of the elite have forgotten that the social contract goes both ways,” she said. “It’s not in their interest to create a nation of renters — maybe it’s in their short-term interest. When you make people live in a more precarious situation, that makes it a more dangerous country for everyone.”

For Price, the numbers tell the same story in economic terms.

“Income over time converts into wealth,” he said. “The slower pace of growth for incomes below the 90th percentile has meant that it is harder for that population to save up enough for things like real estate purchases.”

Both experts agree that unless wages reflect the broader growth of the economy, the housing market will continue to tilt toward investors, not families — and the American ideal of ownership will continue to fade.

As Kilgour put it, “Home ownership is partly about having a sense of dignity and stability — and when that’s stripped away, we all pay the price.”

------------Read More

By: Jonathan Delozier

Title: The $79 trillion shift: How lost wages are fueling the housing crisis

Sourced From: www.housingwire.com/articles/the-79-trillion-shift-how-lost-wages-are-fueling-the-housing-crisis/

Published Date: Fri, 17 Oct 2025 20:58:24 +0000

.png)