The transparent box is the ideal of modern living, but hardly ideal for modern living.

I started writing about residential design just a few months before Dwell published its first issue, and I’ve seen a lot of trends come and go in the last quarter century. Tuscan kitchens gave way to farmhouse kitchens; an interior furnished like a Belgian monastery would be a cottagecore fantasy today; formal dining rooms have become home offices. Even movements that once seemed unstoppably American, like the increasing footprint of the average new house, have revealed themselves to be conditional.

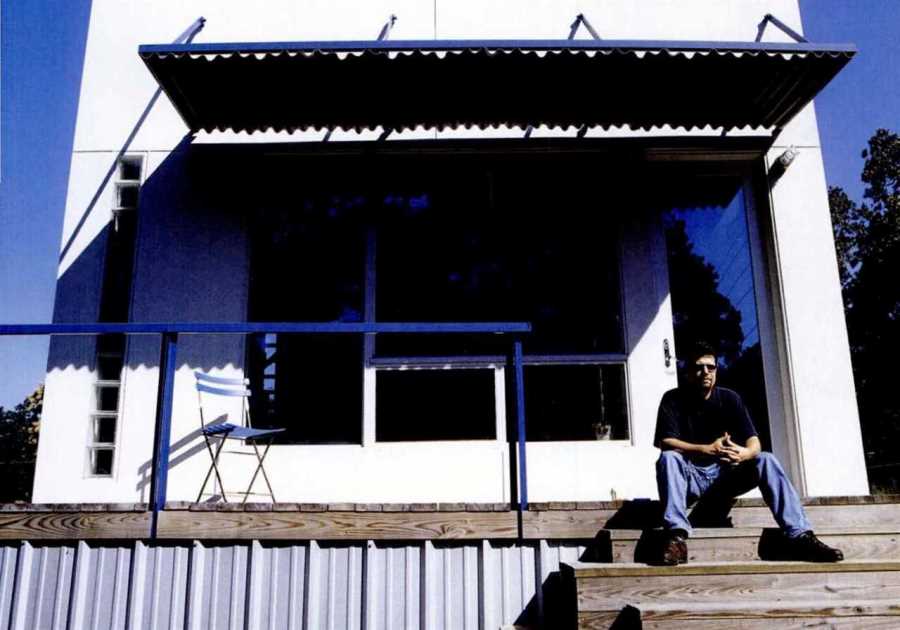

The desire for glass is another one of those unwavering patterns in modern home design that turns out to be less than gospel. Glass houses aren’t as covetable as they used to be, and you don’t have to simply take my word for it. This is a trend you can find in Dwell’s archive. The low-slung, see-through volumes that the magazine championed at its launch—the antidote to Y2K McMansions—have since been replaced by color-drenched interiors, fluted millwork, and terrazzo surfaces.

Unlike building size, which cycles up and down according to cost, the decline of glass houses isn’t so easy to explain. I’ve noticed their ebbing popularity since before the pandemic—and certainly after, too, when breakdowns in the supply chain caused the price of windows and glass doors to skyrocket. Are homebuyers not interested in the vibe glass houses are selling? Or is there something larger at play?

How did we get here?

Perhaps we should pan back for more perspective: One day in 1775, Hendrick Martin walked his grown son Gottlieb to the edge of their Hudson Valley farm for a hard talk. Although Hendrick had expanded the family home at the start of the decade, there was only so much room for his new grandchildren. He paced off a lot bordering the old post road for Gottlieb to "swarm for yourself." The following year, Gottlieb fashioned a 24-by-42-foot building from rubble and hand-hewn timber with help from his battle brothers in the Continental Army. About a century after that, Gottlieb’s grandson Edward punched windows into the north- and south-facing walls, built a generously fenestrated wing behind the stone volume, and added a south-facing conservatory to the new annex.

Welcome to the house I share with my husband, Rick, which I would also call a case study in Americans’ relationship with glass. Edward’s renovations represented a national appetite for the stuff, as well as its promise: more daylight, better views.

A railroad engineer and land speculator, Edward had the means to be an early adopter, and all those windows ranked high among hot new tech. Architectural glass was an expensive, mouth-blown import when Edward’s grandfather Gottlieb was alive, and his windows would have been filled with milky discs of crown glass. Edward sourced wavy sheets of cylinder-blown glass for his house additions with an enthusiasm that finance bros might feel for pivoting glass doors and disappearing walls today. Industry’s march toward today’s huge expanses of barely there glass includes several milestones in the meantime, such as the introduction of plate glass and float glass in 1902 and 1959.

These inventions might have been achieved less slowly were it not for the architecture that stoked a desire for sleek indoor-outdoor connectivity. Think the Bauhaus buildings in Dessau, the Barcelona Pavilion, or the Maison de Verre. But for American homeowners, nothing ignited interest like Philip Johnson’s Glass House. When Johnson completed the Glass House in 1949, Architectural Forum told trade readers that the building was instantly epochal: "The industrial age explored working with Nature; the present age explores living with it." Meanwhile, Life magazine proclaimed the residence "one big room completely surrounded by scenery" to its five million subscribers. For voyeuristic flourish it added, "From his fireside a storm is exciting, new snow a lovely miracle."

The desire for glass is another unwavering pattern in modern home design that turns out to be less than gospel.

Both popular and professional camps acknowledged that the New Canaan, Connecticut, residence had its faults as well. "Certainly this is a very special house…but of little use to a typical American family," New York Times home editor Mary Roche wrote of its lack of privacy. Forum admitted that Johnson’s achievements were more symbolic than functional—and advised the archetypal family to spend most of its time in the adjacent, nearly windowless Brick House that the architect had completed simultaneously.

Perhaps because the acclaim was measured, this first golden age of glass houses didn’t last long. Houston-based architect Troy Schaum, who designed a Shenandoah Valley house featured in these pages two years ago, cites 1962 as a turning point. That’s when Robert Venturi began building a house for his mother that Schaum calls "a kind of response to the functional prowess that architects were demonstrating with the Miesian dematerialization. Postmodernism followed on Venturi’s thoughts about the frontality and image of a building."

The pendulum swings twice

The glass house returned to vogue three decades later. Sure, up-and-coming tastemakers had rediscovered midcentury design as an antidote to PoMo. Makers of architectural glass had also worked out its insulation, acoustical, and engineering kinks, making it possible to inhabit a cloche as luxurious in comfort as in appearance. In 2013, architects Arjun Desai and Katherine Chia revealed the potential for utmost comfort when their eponymous studio completed a 21st-century Farnsworth House not far from Rick and me. Called the LM Guest House, this homage to the Mies van der Rohe–designed residence—after which Johnson modeled his own project—resolved the performance blind spots of yore with triple-glazed float glass, geothermal heating and cooling, and motorized shades, among other things. It’s also not a fishbowl, thanks to discreet siting on 365 rolling acres.

It sounds like the best of all worlds, so why haven’t LMs proliferated across the contemporary landscape? Chia says she still fields plenty of requests for exquisite glass boxes but often redirects clients to other options. That’s in part because sustainable building has become so mainstream. "LM abides by an older energy code, and nowadays it’s much more restrictive," she tells me. "To do an all-glass house in California is pretty tough, and other states are following suit." I share this feedback with Schaum, who seconds the observation. Making a glass house has "only gotten more complex in the way the facade has to perform," he says.

In addition to better energy performance, architects have reasons to envision a life with more opacity. Leigh Salem, founding partner at Brooklyn- and Jackson, Wyoming–based Post Company, says, "We’re thinking about spaces that clients can grow into and that their kids and grandkids inhabit." That kind of future-proofing is easier to achieve by "cutting a hole into a wood-stud wall" than by modifying a highly engineered glass house. Salem adds that homeowners-to-be are more easily steered away from Farnsworth and Glass House tributes than ever, too. "People are less interested in exposure and more interested in privacy, even rejecting the open floor plan," he notes.

There’s no guaranteed rule for placing windows and doors in this era of judiciousness. The largest expanses of glass may be reserved typically for living and dining rooms, since passersby likely won’t catch you dancing in your undies in these spaces. A generous east-facing kitchen window also can be typical, to suffuse morning routines in daylight. But all kinds of exceptions apply to both rules of thumb: new construction versus renovation, a better vista elsewhere, nosy neighbors, a desire to break convention.

Back at the Martin homestead, exceptions rule. Over the last five years and counting, Rick and I have been reconstructing the building with a decent amount of historical fidelity. Gottlieb’s squattish stone cottage looks and feels much as Edward left it, while Edward’s wing is slightly rearranged inside and contains the up-to-date systems that neither patriarch could have imagined. Meanwhile, instead of resurrecting the conservatory, which may have disappeared at some point before the Depression, we transformed a corner of the back porch into our own glass box: double-glazed for decent performance, muntined for historical sensitivity, and sheathed inside with wood blinds for some extra privacy from the raised ranch next door. Like the homeowners before us and probably like the ones who will follow, Rick and I crave sunshine and views, and we’ve figured out a way to suit that aspiration to this site and our budget, as well as to the community and moment we occupy. And whether you’re an architect or a homeowner, a devotee of glass boxes or private hideaways, aren’t we all looking for a perfect fit?

—

Head back to the July/August 2025 issue homepage

Read More

By: David Sokol

Title: The Case Against Glass Houses

Sourced From: www.dwell.com/article/the-case-against-glass-houses-c705da20

Published Date: Tue, 08 Jul 2025 12:02:19 GMT

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginbusiness.business/real-estate/this-glassy-getaway-in-the-mountains-of-japan-is-not-your-typical-cabin

.png)