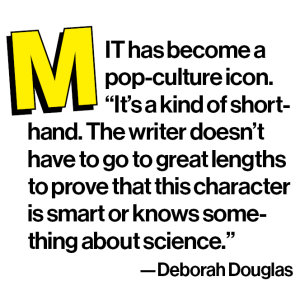

In a workshop filled with robotic limbs and several expensive cars, the clanging of a hammer rings out over the blasting sounds of AC/DC. Amid the clamor, a man with a glowing arc reactor in his chest is hard at work with help from J.A.R.V.I.S., an AI program of his own creation. On the man’s right hand shines a golden brass rat.

Tony Stark, better known as Iron Man, is perhaps the most iconic representative of MIT in Marvel comics and movies. In Iron Man’s first appearance, in Tales of Suspense #39 (1963), the millionaire inventor of high-end weapons and CEO of Stark Industries is kidnapped by a warlord who wants him to build a superweapon. After crafting an armored robotic suit instead—a suit that allows him to escape his captors—he realizes the harm his company is inflicting. So Stark eventually shifts his focus to more humanitarian projects and embraces the persona of a tech-assisted superhero.

The brass rat Stark wears in the 2008 movie Iron Man is no coincidence. Readers of the 1996 comic Iron Man: The Legend learn that he graduated from MIT at 17 with a double major in physics and engineering—an impressive but not completely beyond-the-realm-of-possibility feat at MIT in real life. (His status as valedictorian and summa cum laude graduate, however, is of course pure fiction; the real MIT doesn’t bestow these honors.)

The Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) packs in multiple additional references to Stark’s MIT education. In Iron Man, a montage shows Stark on the cover of MIT Technology Review as a student, and the Institute calls on him to give a commencement speech; in Captain America: Civil War, Stark establishes the September Foundation, which funds the education of prodigies, in an MIT auditorium that looks a lot like Kresge. He also meets his best friend, James Rhodes, at MIT; both are seen wearing the iconic MIT rings known as brass rats in Iron Man. It’s likely that Marvel’s writers gave Stark an MIT backstory to make his creation of such a sophisticated full-body robotic suit seem plausible, since such technology is as yet unachievable in the real world.

How did MIT come to symbolize technological genius? While it may seem strange to ask such a question, the Institute wasn’t always as famous as it is today. “Scientists, engineers, and industrial leaders of course knew of MIT, but widespread public attention really accelerated in the mid-20th century,” says Deborah Douglas, director of collections and curator of science and technology at the MIT Museum. Doc Edgerton’s famous high-speed photos, MIT’s role in the development of radar during World War II, and the Instrumentation Lab’s contributions to the Apollo space program in the 1960s raised the Institute’s public profile, as did WGBH’s television series MIT Science Reporter in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Then media coverage of the MIT Daedalus Project, which in 1988 re-created the mythical flight of Daedalus by flying a human-powered aircraft between the islands of Crete and Santorini, “began to create awareness that extended well beyond the Boston Globe or the usual publications,” she says. “MIT had never received that kind of public attention, and it vaulted the Institute into a level of public recognition globally that it had never known before.”

As MIT has become more widely known, it has also become a pop-culture icon. “It’s a kind of shorthand,” Douglas says. “The writer doesn’t have to go to great lengths to prove that this character is smart or knows something about science, at risk of boring the audience.” Marvel in particular uses this MIT shorthand to make fantastical technology, such as arc reactors and robotic suits that give their wearers the ability to fly, seem believable. Having an MIT genius behind these creations is an easy way to explain the unexplained. That’s particularly useful for comic book writers, who need to say a lot in a few words to leave plenty of room for illustrations.

The convenience of the “MIT = genius” trope—and the popularity of Iron Man—led Marvel to create two other MIT heroes with robotic suits who recently made appearances on the silver screen.

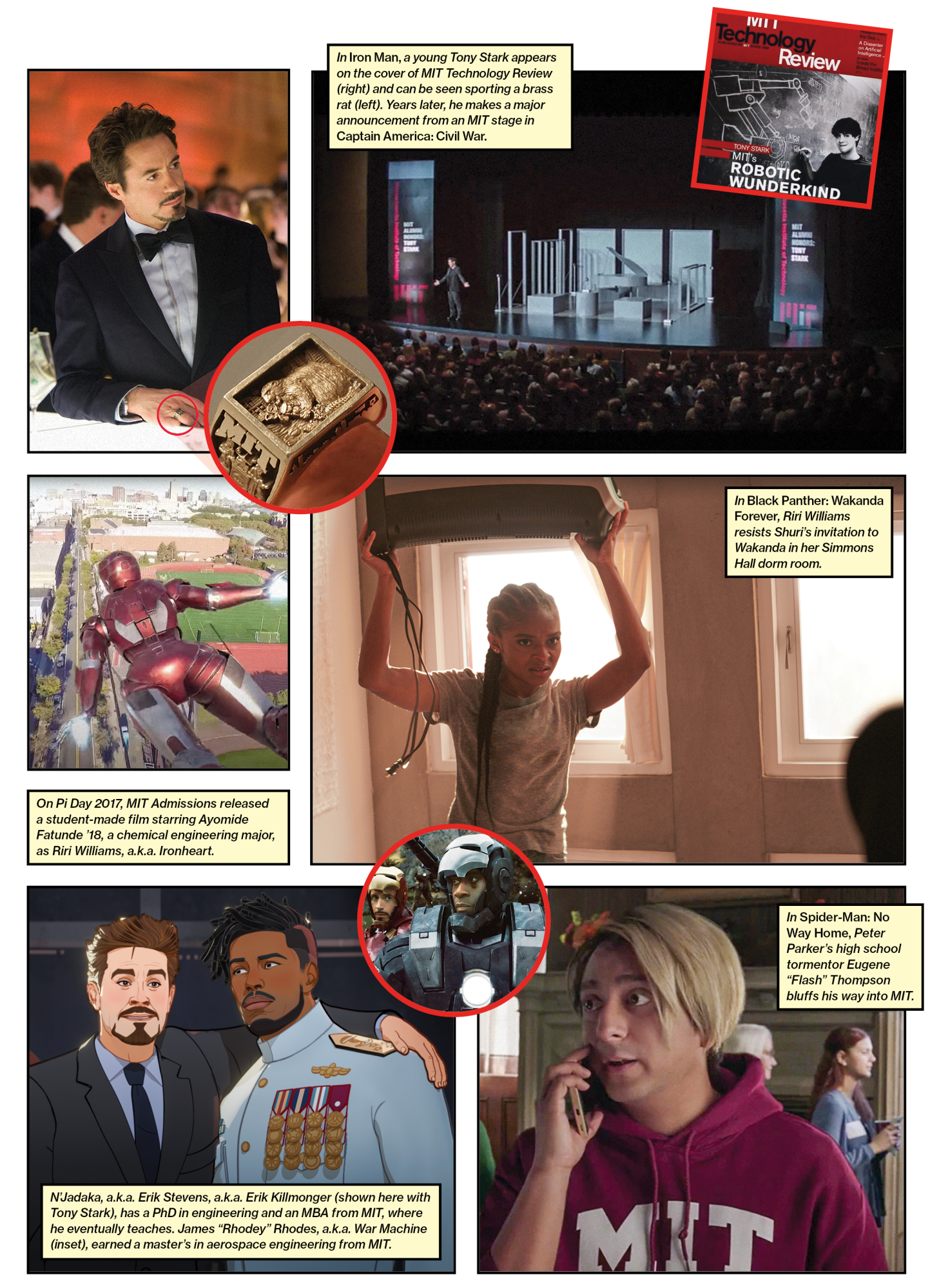

Shortly after being unmasked as Spider-Man and accused of murdering Mysterio, Peter Parker swings into a coffee shop, a piece of mail clutched tightly in his hand, to find his friends MJ Watson and Ned Leeds so they can all open their letters from MIT Admissions together. Their anticipation fades as they read, “In light of recent controversy, we are unable to consider your application at this time.”

In Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021), Parker—a.k.a. Spider-Man—was confident that, having been mentored by Tony Stark, he had a good shot of getting into MIT. With access to Stark’s resources, Parker had gone from using homemade web shooters to designing a suit enhanced by nanotechnology. And he certainly had the academic credentials, having attended the highly competitive (fictional) Midtown School of Science and Technology and developed his skills as Spider-Man. So when he isn’t accepted, Parker launches a crusade to have MIT Admissions reconsider. The movie’s plot aligns with the reality that MIT does not consider a student’s connections or legacy status in admissions decisions. As Chris Peterson, SM ’13, of the MIT Admissions Office explained in a 2012 blog post, “There is only one way into (and out of) MIT, and that’s the hard way.”

Another Iron Man protégé didn’t try to use the superhero’s help to get into MIT because she had already been a student there before meeting him. In Invincible Iron Man Vol. 3, #7 (2016), 15-year-old Riri Williams works late into the night in Simmons Hall, making a replica of the Iron Man suit. Much to the dismay of campus security, Riri helps herself to property from a robotics lab, skips classes, and draws several noise complaints for her work. To avoid repercussions, she flies off in her suit, meets Iron Man, and earns the moniker Ironheart. In real life, Marvel arranged to temporarily close Massachusetts Avenue in 2021 to film several scenes—including some with Riri—for Black Panther: Wakanda Forever. The character is slated to have her own show on Disney+, but the timing of its release is uncertain, given the strikes in Hollywood.

In between Tony Stark and Riri Williams, another set of MIT students also made a brief appearance in the Marvel universe.

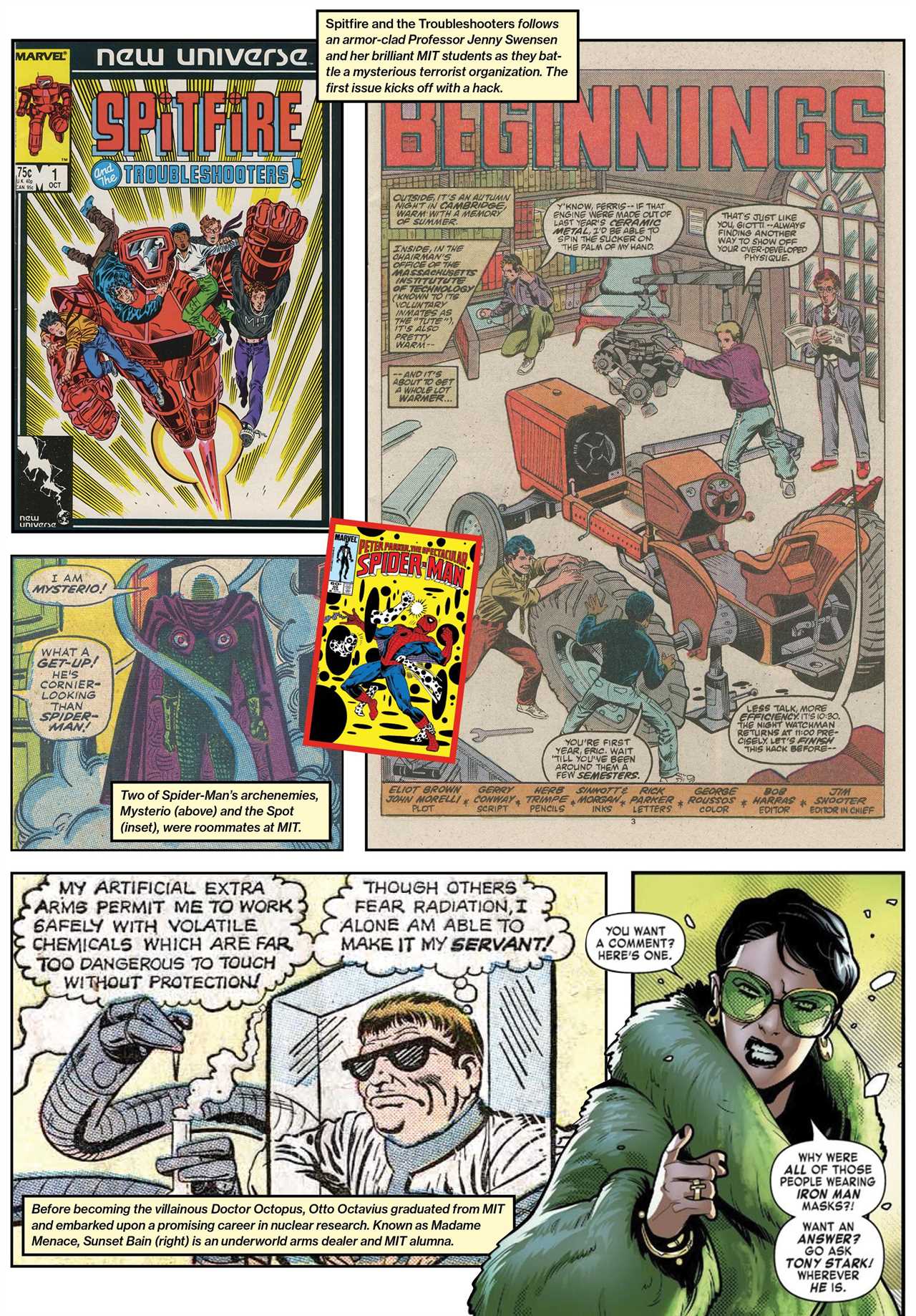

One late autumn night in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the MIT chairman’s office is abuzz with activity. It is not occupied by its owner, but instead by a group of students and a half-assembled tractor. Despite their precautions to avoid the night watchman, their professor catches the hackers mid-prank—and distracts the approaching chairman so that they can flee on the ledges of the building’s exterior.

Nearly 20 years after Iron Man’s debut in the comics but long before he showed up on the silver screen as an MIT alum, MIT figured prominently in another Marvel series. Spitfire and the Troubleshooters, a short-lived 1980s title, introduces readers to a motley crew of five MIT undergraduates and their structural engineering professor, Jennifer Swensen. The students, known as the Troubleshooters, assist Swensen in her quest to rescue the robotic “Spitfire” suit that her father invented to help construction workers—before it becomes militarized by her father’s murderer. To do this, the Troubleshooters draw upon their hacking skills, which they’d previously honed to construct that tractor and later to sabotage the opposing crew team during an MIT-Yale race.

The hacking hijinks chronicled in Spitfire and the Troubleshooters were inspired by author Eliot R. Brown’s trips to MIT to visit a student who’d been his childhood friend. During those visits, they “would run around on the rooftops” and “break into rooms and swipe ladders and climb up the sides of buildings,” Brown told the comics magazine Back Issue! in 2009. In addition to depicting the MIT campus, Brown and his coauthors aimed to present a more realistic version of the whole robotic-suit idea. “It was more than ‘Iron Girl’—it was a different technological attitude, more reality-based. Iron Man was not unreal, but Iron Man as a concept did too much,” Brown explained in the Back Issue! interview. “I tried to do something that was more of a garbage can with legs and a good brain in it, something more mechanical.” While Brown’s depiction of MIT characters and their exploits was comparatively true to life, some of the Troubleshooters’ actions violate two of the hacking principles listed in MIT’s Mind and Hand Book: leave no damage and do not steal anything. But then again, not all MIT characters in the Marvel Universe have the world’s best interests at heart.

Inside a darkened MIT lab space with a “RESTRICTED” sign on the door, a student is filling chalkboards with complex equations inspired by his classroom lectures. A professor enters the room, outraged at this student’s unauthorized presence. But the ingenious calculations on the wall draw him to halt and lead him to offer the student, Otto Octavius, a research opportunity with his lab.

Readers of the Spider-Man/Doctor Octopus: Year 1 comic series learn that Octavius conducted extensive nuclear research while an undergraduate at MIT, just as MIT’s Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP) lets undergrads work on meaningful research in real life. Octavius’s work is funded in part by the government and gives him an accelerated track to a doctorate. But when one of his experiments goes awry, Octavius’s mind is warped, and he gains four robotic arms that assist in his new life of crime as the evil Doctor Octopus (or Doc Ock for short).

Several other Marvel villains also have MIT credentials. In Iron Man Vol. 3 (1999), readers find out that Sunset Bain (Madame Menace) attended MIT at the same time as Stark. Bad guys Quentin Beck (a.k.a. Mysterio) and Dr. Jonathan Ohnn (a.k.a. the Spot, because he can teleport through spots on his body) are noted to have been roommates at MIT in Symbiote Spider-Man Vol. 1, #1. In an alternate universe in the Disney+ show What If … ?, Tony Stark’s friend Rhodey does a background check into Erik Stevens (the villain known as Killmonger) and finds out that he attended MIT.

Like most MIT alumni, these villains have a knack for science and engineering. Mysterio uses chemistry to develop convincing special effects for evil purposes, Killmonger leverages his extensive knowledge of weaponry, and Doc Ock wields his robotic arms to wreak havoc on New York, often attempting to steal research equipment. Since they use their technical skills for evil, it would seem that Marvel villains flout a core tenet of the MIT values statement: “Together we possess uncommon strengths, and we shoulder the responsibility to use them with wisdom and care for humanity and the natural world.”

Not all these evil characters with MIT backstories are doomed to a life of villainy, though. In one story arc from 2013, Octavius switches minds with Peter Parker to escape his imminent death from cancer. But with the dying wish of Parker, Octavius adopts a new identity as Superior Spider-Man. In this second chance at life, he founds Parker Industries, a conglomerate whose work includes developing cybernetic prosthetics and biomedical devices, and finds a girlfriend, Anna Maria Marconi. Long after Octavius relinquishes Parker’s body to its original host to save Marconi, she asks Parker if Octavius was “a good man who did bad things, a bad man who did good things, or a bit of both.” Complex and nuanced characters like this show that even those with a track record of evil have the potential to change their ways and contribute to the world.

Marvel’s sometimes extreme versions of MIT students make for engaging, and often inspiring, stories. And the Institute’s prominent role in the Marvel Cinematic Universe has clearly evoked pride in the MIT community. In 2019, students adorned the Lobby 10 dome with the Captain America shield when Avengers: Endgame hit the theaters. And in 2022, they raised Wakanda Forever banners above the entrance at 77 Mass. Ave. to mark the release of the Black Panther sequel. Riri Williams, who appears on murals around campus and is depicted on the Class of 2020 brass rat, was featured in the MIT Admissions Office’s Pi Day 2017 video (in which she was played by Ayomide Fatunde ’18), generating a lot of media coverage and breaking Admissions Office video viewership records. Several professors have also referenced Marvel in their class assignments. For example, in 2023’s 2.007 Design and Manufacturing class, students designed robots that competed in a challenge called Machina Forever. When Wakanda Forever was released, the MIT Lecture Series Committee screened it in 26-100, and class councils rented theaters to see the film. And Robert Downey Jr., the actor who played Iron Man, visited campus—and met with Professor Hugh Herr in MIT’s Y. Lisa Yang Center for Bionics—in the summer of 2022.

The real-world impact of MIT’s recurring role in Marvel story arcs goes beyond scenes filmed on campus and Marvel-inspired hacks. The complexity of the MIT characters reminds viewers and readers that not all MIT students are cut from the same cloth. And the range of heroes, villains, and those in between shows that everyone can make an impact. But equally important, stories like those of Iron Man, Riri, and the Troubleshooters counterbalance what can be the unglamorous reality of working to advance knowledge and educate students. These tales highlight what is exciting about science and technology—and just might inspire the inventors and innovators of tomorrow. As Douglas says, “We don’t like our stories about committees. We like our stories about heroes and heroines.”

------------Read More

By: Jade Durham ’25

Title: Superhero U

Sourced From: www.technologyreview.com/2023/10/24/1081048/superhero-u/

Published Date: Tue, 24 Oct 2023 21:00:00 +0000

.png)