A year before his death, the visionary designer and his disciples reflected on how he created some of the most intimate, functional, and comfortable outdoor spaces imaginable.

As a part of our 25th-anniversary celebration, we’re republishing formative magazine stories from before our website launched. This story previously appeared in Dwell’s September 2007 issue.

If you’ve ever wondered what it might feel like to picnic, play, or wander through a painting by Jean Arp, Joan Miró, or Wassily Kandinsky, you might try visiting a private or public garden designed by Robert Royston.

Instead of seeking inspiration from formal French or Italianate gardens or English estates—the norm when Royston was a student in the late 1930s— he transformed modern art’s geometric lines, overlapping planes, and biomorphic curves into some of the most intimate, functional, and comfortable outdoor spaces imaginable.

"I was always consumed with the way space moved, be it a painting, a sculpture, or the outdoors," recalls Royston, still vibrant and dapper at 89, with the warm demeanor and sparkling blue eyes of a family doctor as depicted by Norman Rockwell. As a student in landscape architecture, he took his site plans to the art department for criticism. As a teacher, he designed a special transparent "model box" to help his students manipulate images in order to consider the psychological impact of a space: How would it feel if it were narrower, sunnier, more enclosed or exposed?

Photos courtesy RHAA

"Bob is one of the most important pioneer modernists in landscape architecture," says Reuben Rainey, coauthor with JC Miller of Modern Public Gardens: Robert Royston and the Suburban Park. "His work is derived from avant-garde painting and sculpture, but the form-giving was always based on the needs of the individual users. So many parks are just a scattering of equipment; his designs are truly spatial and reflect a deep understanding of human interaction."

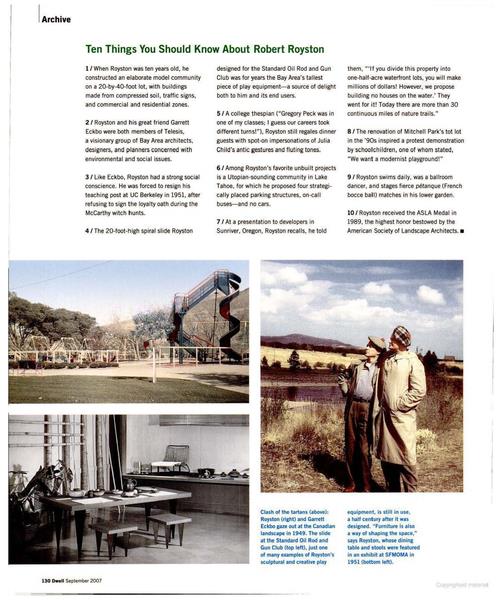

Royston got his modernist feet wet in 1938 while a student at the University of California at Berkeley, apprenticing in the office of Thomas Church. A few years later, as a boat commander in the navy and witness to carnage he couldn’t talk about for years, the nights kept him sane. "I would creep into my office and dream about landscape architecture, sketch houses, make jewelry," recalls Royston, who is also a lifelong painter.

Back in the Bay Area after the war, Royston resumed his friendship with Garrett Eckbo—who had shaken things up, design-wise, with Dan Kiley and James Rose at Harvard—and the two, along with Edward Williams, set up the firm Eckbo, Royston, and Williams. (After an amicable split in the late ’50s, Royston founded the firm that became Royston, Hanamoto, Alley & Abey.) Royston and Eckbo shared not only an aesthetic approach, but a belief that design could have a positive impact on people’s lives. Royston once wrote: "We work in the realm of health: our profession can restore a marsh, purify the air, abate noise, and provide systems in the city where trees will grow and people can gather, exercise, and laugh."

"Bob’s goal was to get people outdoors," says JC Miller. "Lots of his early work was on steep sloping lots, and decks gave people usable space. Today, sliding glass doors and decks are taken for granted, but when he was starting out, this was revolutionary." Royston’s artistic sculpting of the space—with overlapping planes of paving, decks, and benches often sheltered beneath one of his circular suspended umbrellas—created graphic compositions that were inviting and functional, and just as compelling when viewed from above.

Photos courtesy RHAA

One of Royston’s living laboratories is his home in Mill Valley, California, designed 60 years ago by former office mate and Bay Area modernist architect Joseph Allen Stein. Recalls Royston: "I looked over his shoulder at a house he was designing for himself, and I liked it. So I bought half his property and did a reverse plan in exchange for doing his garden. It was a good deal!"

The concrete-slab dwelling, filled with art and paneled in wood with a rolled-copper-covered fireplace, has a triangular central living area that opens to the outside through walls of glass. The gardens seem to lap around and up to the house. "The gardens are extensions of the house," says Royston, who still takes pleasure in pointing out how the polished-concrete flooring aligns with the pavers across the threshold. The main terrace flows into a bench-lined deck that extends, pier-like, toward Mount Tamalpais, and is furnished with tables tiled by Royston’s friend, the renowned ceramicist Edith Heath. The rose garden, planted in rolling pots of Royston’s design and tended by his wife, Hannelore, sits behind a screen embedded with panels by artist Florence Swift that Royston created for SFMOMA.

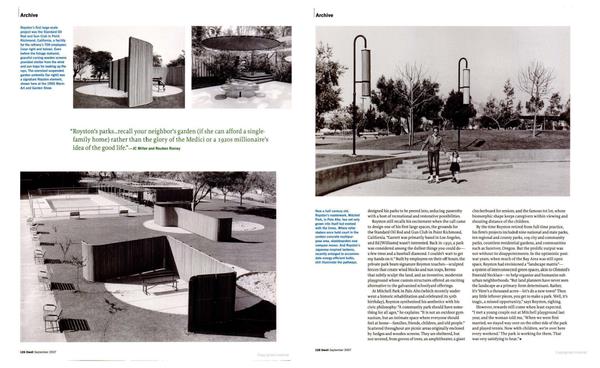

Many of Royston’s techniques in private gardens—the intimate spaces, undulating walls, vine-smothered pergolas, screens, and places to eat and play—carried over into his suburban parks, albeit on a larger scale. Never merely ornamental, the Mondrianesque paving patterns and furnishings helped shape the space and define zones until the foliage matured. And unlike the urban pastorals of Frederick Law Olmsted, for example, where plantings create a green buffer between park and street, Royston designed his parks to be peered into, seducing passersby with a host of recreational and restorative possibilities.

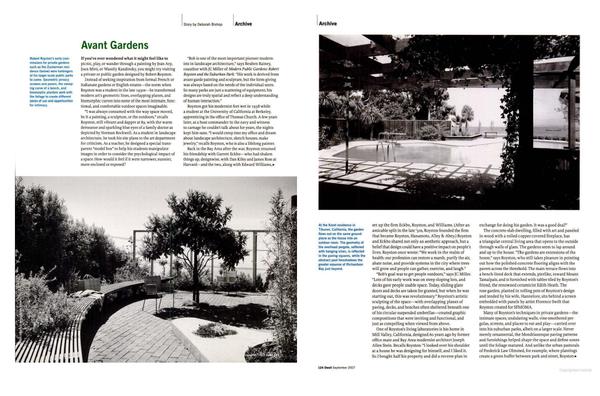

Royston still recalls his excitement when the call came to design one of his first large spaces, the grounds for the Standard Oil Rod and Gun Club in Point Richmond, California. "Garrett was primarily based in Los Angeles, and Ed [Williams] wasn’t interested. Back in 1950, a park was considered among the dullest things you could do—a few trees and a baseball diamond. I couldn’t wait to get my hands on it." Built by employees on their off hours, the private park bears signature Royston touches—sculpted fences that create wind blocks and sun traps, berms that subtly sculpt the land, and an inventive, modernist playground whose custom structures offered an exciting alternative to the galvanized schoolyard offerings.

At Mitchell Park in Palo Alto (which recently underwent a historic rehabilitation and celebrated its 50th birthday), Royston synthesized his aesthetics with his civic philosophy: "A community park should have something for all ages," he explains. "It is not an outdoor gymnasium, but an intimate space where everyone should feel at home—families, friends, children, and old people." Scattered throughout are picnic areas originally enclosed by hedges and wooden screens. They are sheltered, but not severed, from groves of trees, an amphitheater, a giant checkerboard for seniors, and the famous tot lot, whose biomorphic shape keeps caregivers within viewing and shouting distance of the children.

By the time Royston retired from full-time practice, his firm’s projects included nine national and state parks, 10 regional and county parks, 109 city and community parks, countless residential gardens, and communities such as Sunriver, Oregon. But the prolific output was not without its disappointments. In the optimistic postwar years, when much of the Bay Area was still open space, Royston had envisioned a "landscape matrix"—a system of interconnected green spaces, akin to Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace—to help organize and humanize suburban neighborhoods. "But land planners have never seen the landscape as a primary form determinant. Rather, it’s ‘Here’s a thousand acres—let’s do a new town!’ Then any little leftover pieces, you get to make a park. Well, it’s tragic, a missed opportunity," says Royston, sighing.

However, rewards still come when least expected. "I met a young couple out at Mitchell playground last year, and the woman told me, ‘When we were first married, we stayed way over on the other side of the park and played tennis. Now with children, we’re over here every weekend.’ The park is working for them. That was very satisfying to hear."

Photos courtesy RHAA

See the full story on Dwell.com: From the Archive: How Robert Royston Became a Pioneer of Modernist Landscape Architecture

Related stories:

- From the Archive: How Konrad Wachsmann Became a Prefab Pioneer

- The Rise of Co-Buying Has Queer Roots

- From the Archive: Floating on Air in the Tradition of Lautner’s Chemosphere

Read More

By: Deborah Bishop

Title: From the Archive: How Robert Royston Became a Pioneer of Modernist Landscape Architecture

Sourced From: www.dwell.com/article/from-the-archive-how-robert-royston-became-a-pioneer-of-modernist-landscape-architecture-0ed6e7b6

Published Date: Thu, 14 Aug 2025 16:11:15 GMT

.png)