Mortgage-pricing data has gone digital. But when does transparency turn into coordination?

In early October 2025, mortgage-technology provider Optimal Blue and three major lenders were sued in a proposed class-action alleging price-fixing and market manipulation in U.S. mortgage rates. At the center of the case is a question that goes well beyond one software firm: when does sharing data make markets fairer, and when does it quietly tilt them?

Optimal Blue’s software powers pricing for roughly one-third of U.S. mortgage lenders. Each participating lender uploads the rates they charge on every loan into the company’s pricing engine. Those rates become visible, often in near-real time, to other lenders using the same system.

The value proposition is obvious. By pooling information, lenders can see how their peers are pricing and adjust accordingly. The lawsuit claims that this visibility allowed lenders to “flex” prices upward in unison, creating implicit coordination that harmed borrowers.

Critics call that algorithmic collusion. Supporters call it benchmarking, a standard feature of efficient markets.

What counts as manipulation?

Market manipulation traditionally means deliberate interference in price discovery, that is, creating artificial or distorted prices to gain advantage. That can mean pump-and-dump schemes, bid-rigging, or spreading false information.

But the definition becomes hazier in data-driven markets. If a tool merely shows competitors’ prices, and each actor adjusts independently, is that manipulation or competition?

The case against Optimal Blue echoes a pattern that has appeared across industries where data and algorithms mediate pricing. For example, the revenue-management software of RealPage faced allegations of keeping rents higher than a truly competitive market would. Credit-scoring via FICO relies on pooled data to set risk-based pricing.

Stock markets share bid/ask data, and retail investors benefit from that transparency even though large players use faster algorithms. As visible households now own more stocks than ever before due to the perceived risk-return, lower commissions on trading and performance of the market. All possible through digitization and data standardization. If we were still using punch cards would this outcome be possible?

Each of these examples raises the same tension: data that improves efficiency for one group may look like coordination to another.

Competition, scale, and the benefits of data

Critics argue that pooling mortgage-data dulls competition. Advocates counter that the same tools level the field for smaller lenders, giving them access to insights that only giants once held.

History suggests transparency usually lowers costs, not raises them. For example, stock-trading fees have fallen to near-zero as market data and electronic trading expanded. If data pooling were inherently anticompetitive, the trend would go the other way.

Large lenders still enjoy advantages: lower funding costs, stronger balance sheets, cheaper execution — but those are structural, not conspiratorial.

Consider corporate debt. Apple Inc. has a senior unsecured long-term credit rating of Aaa from Moody’s and AA+ from S&P Global. (Barron’s) Because of that rating and its robust liquidity, Apple is able to issue bonds with yields around 4.9% for certain maturities. (Barron’s) That difference exists because investors have data on defaults and recoveries. Without pooled credit data and market data, every borrower would be treated equally. The result would be either: everyone paying higher rates to cover unknown risk, or lenders mis-pricing and losing money.

Pooling data reduces systemic uncertainty. That is what makes markets work.

When does data cross the line?

Data becomes manipulative when it limits independent decision-making, distorts supply and demand signals, or operates during extreme cycles.

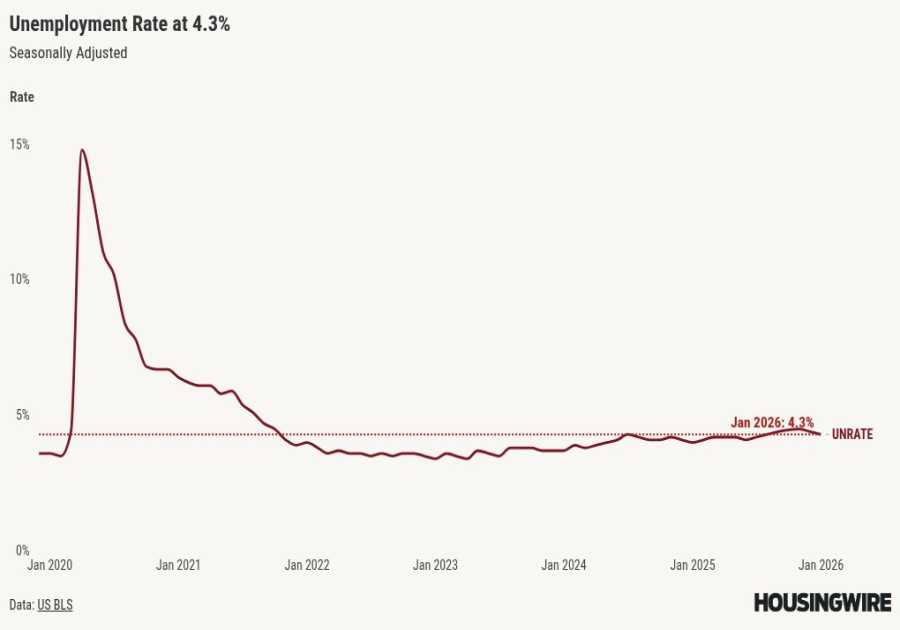

After COVID-19, record liquidity and cheap capital fueled a housing boom. Home prices and rents surged. In that environment, any pattern of shared pricing, even if unintentional, looks suspect. During stable markets, data looks efficient. During bubbles, it looks conspiratorial.

Source: Mortgage Professionals

As affordability fell sharply and public tolerance for persistent prices percolated into antipathy for algorithmic pricing, the same data-sharing tools once praised for precision now faced scrutiny for fairness. Regulators, sensitive to political pressure, may treat coordination through shared data as collusion even if the mechanism mirrors accepted benchmarking elsewhere in finance.

CoStar and the real estate market

CoStar Group controls 20% of the rental-listing market through Apartments.com. By aggregating listings, rents, and transaction data, it effectively “makes the market” for multifamily housing and single family. In fact, per CoStars presentation, member agents sell homes faster than non-member agents. So pooled data provides advantages, which is evident in a better, more efficient market to those who access it. This is a classic example of a market economy.

Is that manipulation? Not by traditional standards. Its dominance creates information asymmetry, but not necessarily collusion. The data is available to all paying users.

The distinction lies in use. If data improves transparency and enables competitive pricing, it drives efficiency. If it enables synchronized pricing behaviour, it becomes manipulation.

Efficiency versus exploitation

Data can equalize or cartelize. The difference lies in intent, timing, and access. Are participants sharing data to compete or to protect margins? Is the data historical or real-time? Is it open to all or selective?

Economists call this the information-efficiency paradox: more data usually helps markets, until it helps everyone behave the same way.

Markets depend on price-discovery, and price-discovery depends on data. Mortgage rates, rents, bond yields, and stock prices all rely on aggregated signals. Without them, markets would freeze.

But as AI and analytics connect those signals more tightly, the line between insight and interference narrows. The Optimal Blue case is not just about mortgages. It’s about how society defines fair competition in an algorithmic era. If pooling data among lenders is deemed anticompetitive, what does that mean for every other market where data aggregation is standard—from Zillow’s Zestimate to Nasdaq’s quotes?

The alternative : Information asymmetry, which benefits those with scale

Large operators of platforms, such as Amazon.com, have disproportionate access to information due to their scale. If this valuable pricing data is unavailable to a small store, they’re toast. Amazon’s success is due to other factors in addition to snowballing of data, but this is a classic case of data advantage helping an incumbent versus the larger market more broadly.

The takeaway

Pooling data does not automatically mean collusion. It can promote transparency, efficiency, and access for smaller players. Collusion is not always explicit; algorithms can produce collective behaviour without communication.

Context matters. In high-inflation, high-inequality environments, even the perception of coordination draws scrutiny. The Optimal Blue lawsuit may push regulators and courts to define new boundaries for the data economy: not just in mortgages but across every industry where algorithms increasingly determine price, value, and risk.

Vidur Gupta is founder and CEO of Beekin, an AI platform for rental-housing.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of HousingWire’s editorial department and its owners. To contact the editor responsible for this piece: [email protected].

Read More

By: Vidur Gupta

Title: The Optimal Blue lawsuit: Data transparency or market manipulation?

Sourced From: www.housingwire.com/articles/the-optimal-blue-lawsuit-data-transparency-or-market-manipulation/

Published Date: Wed, 05 Nov 2025 08:47:00 +0000

.png)